The intellectual history of Ethiopia and Eritrea: Ge'ez manuscripts and scholars (ca. 200-1900CE)

The unique manuscript collections of Ethiopia and Eritrea written in the Ge'ez script are arguably the best-known works of literature produced in pre-colonial Africa.

While the manuscript cultures of West Africa, East Africa, and central Africa are much better known today than a half-century ago, the Ge'ez manuscripts remain the most extensively studied of the continent's historical archives and they have for long been used to reconstruct the political and social history of the northern Horn of Africa.

This article outlines the intellectual history of Ethiopia and Eritrea focusing on the Ge'ez manuscript collections, the scholars who wrote them, and the learning centers they established across the region.

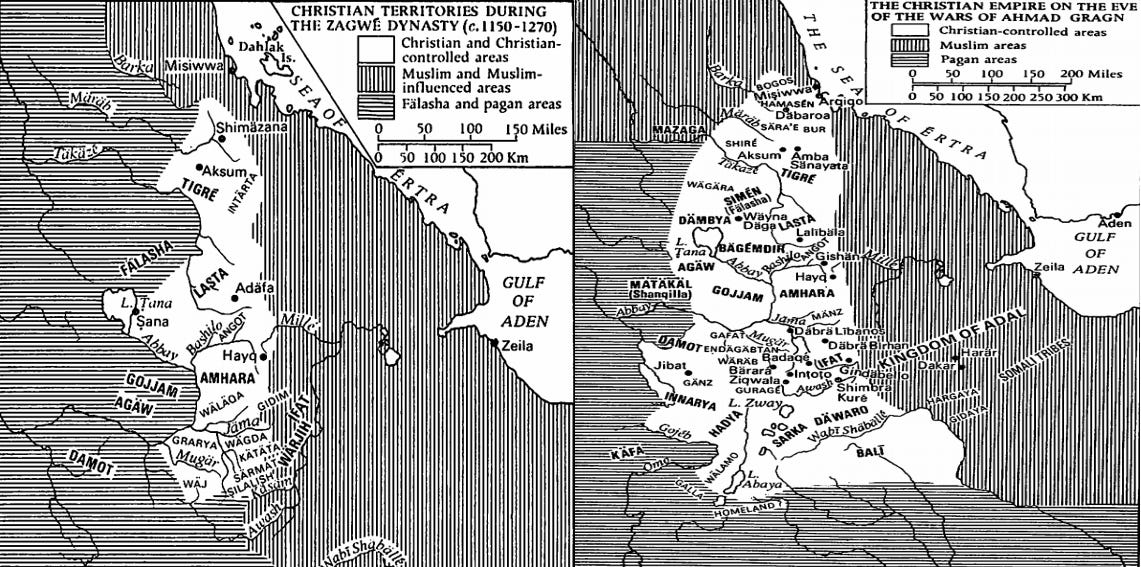

Map of the northern Horn of Africa during the late Middle Ages.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Ge’ez literature during the Aksumite and Zagwe period (ca. 200-1270 CE)

The foundations of Ge'ez literature were established during the pre-Aksumite period (1st millennium BC) and Aksumite eras (50-700CE) when Ge'ez was a spoken language. Proto-Ge’ez names are attested in the inscriptions of the pre-Aksumite period, where they constituted the majority of the names of royals and other elites written in the south-arabian script that was adopted by local elites in the kingdom of D’MT, centered at Yeha in northern Ethiopia1. By the 2nd-3rd century CE, the Ge’ez script had been developed by local scribes to be used in the majority of the earliest Aksumite royal inscriptions, alongside other scripts such as Greek.2

Votive inscription of King Wa’ran son of RD’M and Queen Shakkatum, dedicating the shrine to Almaqah and referring to Yeha. found at Meqaber GaΚewa near Wurqo, Ethiopia. The mention of the king's mother beside his father's name is very unusual in contemporary inscriptions in the south-Arabian script, likely reflecting a local concept of political power.3

The inscription of King Ezana at Aksum in Ge’ez, Greek, and an archaic form of the south-arabian script.4

Besides the inscriptions, a handful of historical and theological writings were preserved from the Aksumite period, the best known of these are the Garima Gospels, which are dated to between 330–650 and 530–660 CE.5 Another recently discovered Aksumite-era manuscript is the Aksumite collection, a 13th-century text from the church of ʿUrā Masqal (in Tigray) that contains compilations of much older works dated to between the 5th and 7th century, that include a History of the Episcopate of Alexandria, and a collection of early theological works translated into Ge'ez from Greek.6

the Abbā Garimā Gospels, digitized by the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library.

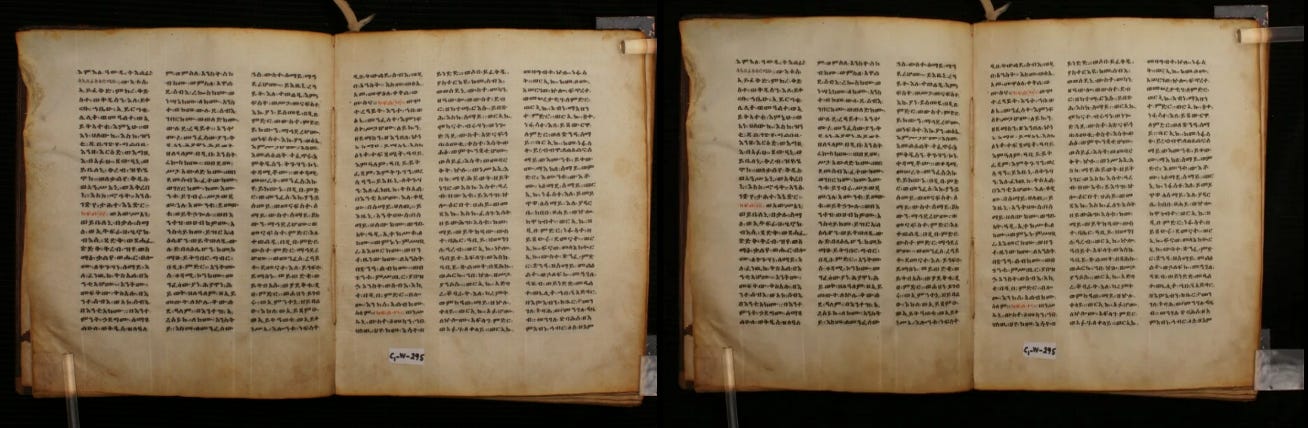

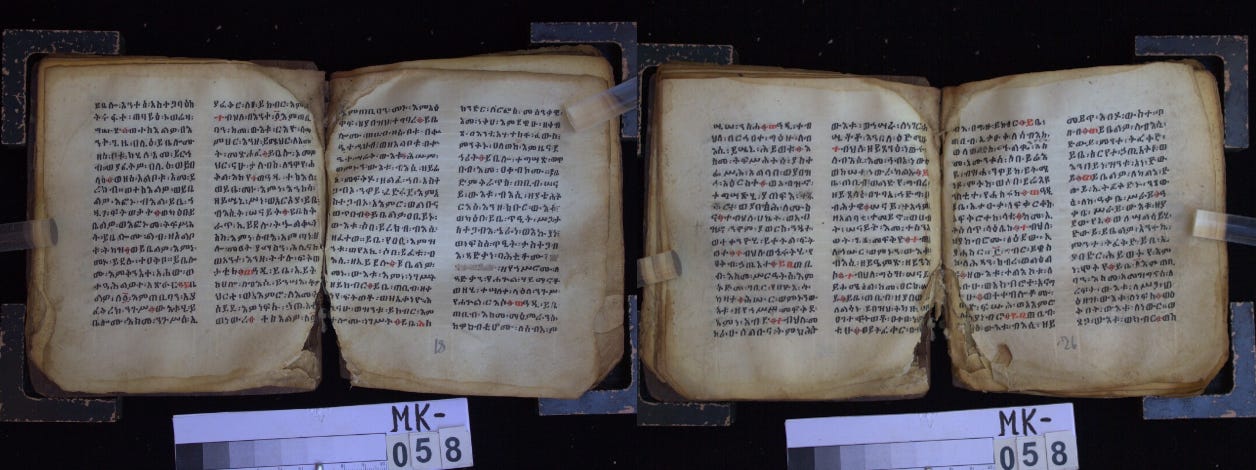

13th-century manuscript copy of the Aksumite Collection, images by Denis Nosnitsin, Ethio-SPaRe.

Abba Garima writing the Garima Gospels. Life and Miracles of Abba Garima, fol. 8v.7

A significant gap exists between the late Aksumite period and the beginning of the Zagwe period where the oldest manuscripts appear around the 12th-14th centuries. They include a land grant to the church of Ura Masqal (Eritrea) donated by the Zagwe king King Ṭänṭäwǝdǝm in the 12th century8, the Four Gospels at Betä MädḫaneʿAläm in Lalibäla and Däbrä Ḥayq Ǝsṭifanos that also contain land grants, both dated to the 13th century, the Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles of Zä-Iyäsus at Däbrä Ḥayq (dated 1292–9), a collection of homilies from Ṭana Qirqos, and other manuscripts from Gundä Gunde and Ǧämmädu Maryam.9

Its likely during the ‘transition’ period between the late Aksumite and Zagwe periods that a number of texts were adopted from the wider Christian world and translated into Ge’ez. These include the Fisalgos, (a classical work of natural philosophy that was translated into Ge’ez from Greek possibly as early as the 7th century10); the Qerellos (a collection of texts written by the early Fathers eg Cyril of Alexandria); and the Book of Enoch, among other texts.11

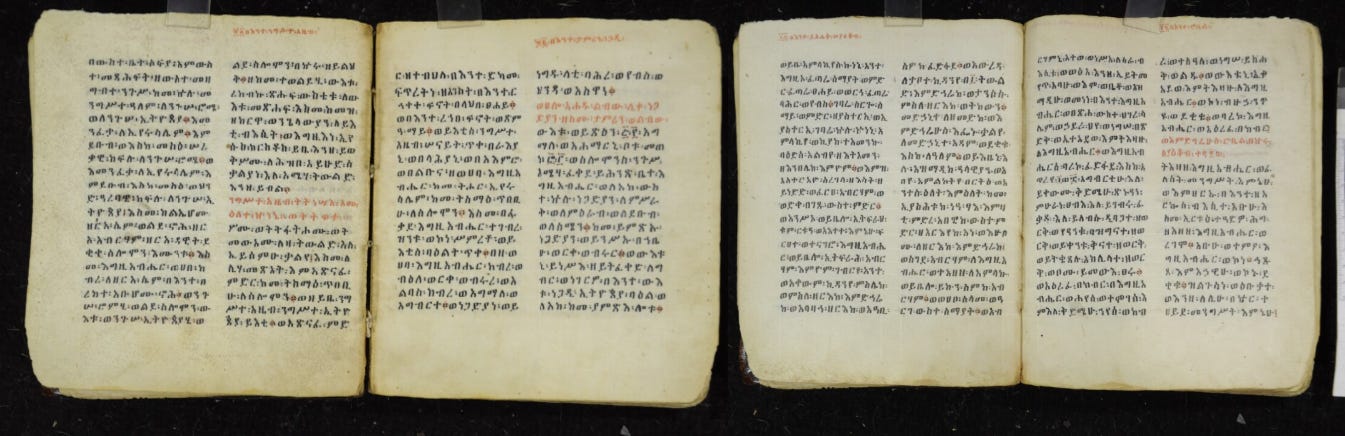

(left) King Lalibela’s 13th-century donation to the Bēta Madòānē ‘Alam à Lālibalā, image by Marie-Laure Derat. (right) pre-14th century copy of the Gädlä Sämaˁǝtat (“Vitae of the Martyrs”) at the church of Ura Mäsqäl, image by ethio-spare.

The Book of Enoch, ca. 1600-1699, Monastery of Marawe Krestos.

Ge’ez literature during the early Solomonic period (1270-1520)

The era following the ascendancy of the 'Solomonic’ rulers marked a significant watershed in the development of Ge'ez literature, especially during the early period (1270-1520)

During this era, the first royal chronicles were produced by scribes who were specially appointed for this task and whose identity is often recorded in the text. These chronicles were mainly concerned with court life, campaigns, political appointments, endowment of churches, settling religious disputes, and other matters. The earliest of the royal chronicles was commissioned by Amda Tseyon (r. 1314-1344), and was followed by the chronicles of the early Solomonid rulers; Zara Yaqob (r. 1434-1468) Baeda Maryam (r. 1468-1478) and Lebna Dengel (r. 1508-1540), as well as a semi-legendary chronicle of Lalibela that was written in the 15th century.12

18th-19th century copy of King Amda Tseyon’s chronicle, d’Abbadie MS. 118, BNF, Paris.

The gospels by Mäṭre Krastos, early 14th century, Church of Saint George in Debre Mark'os, Ethiopia. Library of Congress.

Another important work of Ge'ez literature produced during the early Solomonic era was the Kebrä nägäst (The Glory of the Kings), a national epic written by the scribe Yeshaq of Aksum in 1322 for his patron Ya’ibika Egzi a governor of Intarta (in Tigray), before Amda Tseyon later adopted it to legitimize his power. It’s based on information translated from Coptic-Arabic sources and other accounts and is centered around the meeting of the Queen of Sheba with King Solomon, the birth of their son Menelik I, the transfer of power from ancient Israel to Ethiopia (represented by the moving of the ark), and thus the beginning of the 'Solomonic dynasty'.

the Kebrä nägäst (The Glory of Kings), ca. 1495-1505, Monastery of Marawe Krestos, Ethiopia.

Kebrä nägäst (The Glory of Kings), 17th century, Dabra Koreb We Qeraneyo Medhanealem Monastery

Kings and other elites played a central role in the production of Ge'ez literature as patrons. Scribes associated with the court of Ya’ibika Egzi for example, composed works such as the Mashafa MeStira Samay wamedr (The Book of the Mysteries of Heaven and Earth) and the Zéna Eskender (The History of Alexander the Great), while the generals associated with Amda Tesyon and his successors; [Dawit I (r. 1380-1409), Yeshaq (r. 1412-27), Zar’a Ya‘qob (r. 1433-68), Ba’eda Maryam (r. 1468-78), and Galawdéwos (r. 1540-59)] composed works written in the Amharic language referred to as “soldier's songs” whose contents corroborate the chronicles.13

The translation into Ge’ez of various external writings from the Coptic, Syrian, and Sinai churches was also undertaken during the early Solomonid period, especially in the era of the metropolitan Sälama (1348–1388). These included liturgical books like the Filkesyos and the Coptic Synaxary, the lives of Ethiopian saints (Senkessar), the Senodos (a collection of ecclesiastical canons), the Didascalia, and the Täʾammǝrä Maryam (Miracles of Mary), the Gädlä Kaleb (Acts of Kaleb), etc.14

Senkesar (Lives of saints), ca. 1600-1799, Monastery of Dabra Abbey.

Psalter: Psalms of David and Miracles of Mary in Gee'z, 19th century copy, Brooklyn Museum.

The 15th-century reign of Zärʾa Yaʿǝqob (r. 1434–68) is considered one of the golden ages of Ge'ez literature, with important works being attributed to this period, such as the Fetha nägäst (Law of the Kings), as well as numerous Ge'ez hymns (mälkes) and works of poetry (qenes) and important theological and philosophical texts like the Mäşhafä fälasfa (The Book of the Wise Philosophers)15. Scholars of this period include the king himself, who in collaboration with certain court scribes wrote a number of theological works such as the Mäṣḥafa berhan (the Book of Light), the Mäṣḥafa milad (on nativity), the Mäṣḥafa sellase (book of Trinity), and the Mäṣḥafa Bahrey (Book of the Pearl).16

15th-century copy of the Fetha nägäst (Law of the Kings), with a 17th-century commentary on the text. Dabra Koreb We Qeraneyo Medhanealem Monastery. Motta Giyorgis's private collection.

King Zärʾa Yaʿǝqob’s Mäṣḥafa berhan (the Book of Light), ca. 1495-1505, Monastery of Marawe Krestos.

Fälasäfä (Book of Philosophers), ca 1600-1699, Monastery of Marawe Krestos.

Nägärä Maryam (The Story of Mary), ca. 1360-1399, Monastery of Marawe Krestos.

Various texts of Apocrypha, church administration, and hagiographic works were also written in the period following his reign such as; Gädlä sämaʿǝtat (“Lives of the martyrs”), Gädlä qǝddusan (“Lives of the saints”); the 15th-century hagiographies of Täklä Haymanot (d. 1313), and his successors at Debre Libanos eg Elsa‘a and Filǝṗṗos (ca. 1274–1348); the 16th-century hagiographies of Iyäsus Moʾa of Däbrä Ḥayq Ǝsṭifanos, and Samuʾel of the Waldǝbba monastery. Notable scholars of this period include; Giyorgis of Sägla, who wrote the Mäṣḥafa mestir (Book of the Mystery) and Yǝsḥaq, who wrote the Mäṣḥafä mǝśṭirä sämay wämǝdr (the Book of the mystery of heaven and earth).17

the Mäṣḥafä mǝśṭirä sämay wämǝdr (the Book of the mystery of heaven and earth), 1600-1799, Monastery of Marawe Krestos.

‘the act of St. Takla Haymanot’, copy dated 1700, British Library

Ge’ez literature from the 16th century to the 19th century.

Despite the disruption caused by Ahmad Gran's invasion in the 1520s, Ge'ez literature continued to flourish in the second half of the 16th century. Scholars from this period include; Abba Bahrey (b. 1535) who wrote a rare ethnographic text known as the Zenahu Iägalla (History of the Oromo); and Enbaqom (c. 1470-1560), the etchäge of Däbrä Libanos who in 1540 wrote a theological text titled Anqäsä amin (The Gate of Faith).18

King Gälawdewos (r. 1540–59) also composed theological works defending the Church against the Portuguese Catholics. The most famous of his works was the Confessions, an important text that marked the beginning of a unique genre of related works explaining the Tewahedo dogma such as Queen Säblä Wängel's Fäws Mänfäsawi and works like the Mäzgäbä haymanot (The Treasure House of the Faith), the Mäṣeḥetä lebbuna (The Mirror of the Intellect), the Fekkare mäläkot (The Explanation of the Divinity), among others.19

‘Harp of Praise’, 16th century, Berlin State Library

In the field of historical writing, more royal chronicles were produced during the Gondarine period, such as the chronicles of Gälawdewos (1540–59), Särsa Dengel (1563–97), Susyenos I (1607–32), Yohannes I (1667-1682), Iyasu I (1682–1706), Iyasu II (1730–55), Iyo’as I (1755–69), 20 As well as translations of Coptic works into Ge'ez such as AbuShakir's treatise and the chronicle of Giyorgis Walda Amid.21

Other important genres of Ge’ez literature produced during the Gondarine period include the famous philosophical writings of Zara Yacob and Walda Heywat completed between1668-1693, as well as the numerous land charters and sales, the bulk of which were produced during the “era of Empress Mentewab” (between 1730-1769) and were stored in her church of Qwesqwam, near Gondar. 22

Copy of Zara Yacob’s ‘Hatata’ at the Bibliothèque nationale de France

Land charter of Ashänkera granted by emperor Sarsa Dengel (r. 1563–1597), British library Or. 650 ff 16v. Folio from the 18th century land register at the church of Qwesqwam founded by Empress Mentewab. image by Habtamu Mengistie Tegegne.

History writing would continue during the era of Masanfit after the fragmentation of the Gondarine kingdom, such as the chronicles of the various kings that reigned between 1769 and 1840. 23 more chronicles were written after the restoration of the state by Tewodros II (1855–68), Yohannes IV (1871-1889), and Menelik II (1889-1913), as well as ‘universal histories’ such as that written by Tayyá Gabra Maryam (1860-1924) titled Ya-Ityopaya hazb tarik (‘History of the Ethiopian People”).24

The chronicles of Tewodros II and his successors were written in Amharic rather than Ge’ez, marking a significant shift in the production of Amharic literature which expanded during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, especially in official correspondence and history writing.25 Other written works from this period include theological texts as well as writings on medicine and talismanic/magic scrolls.26

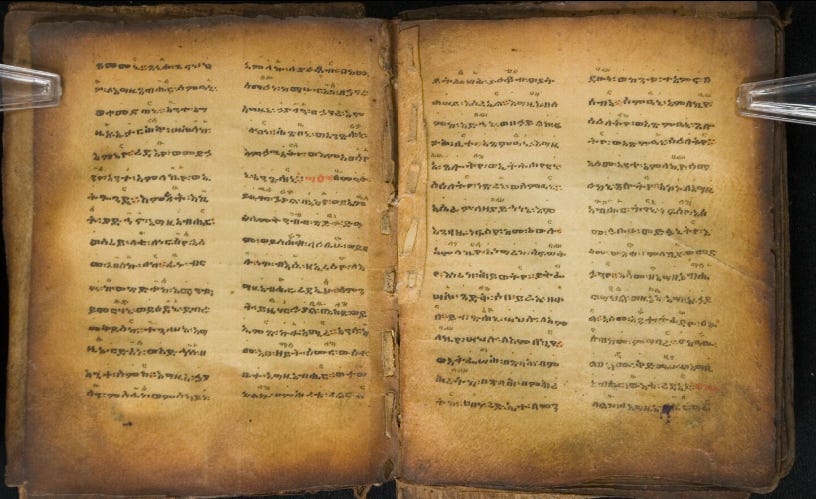

Amharic manuscript on medicine with a list of diseases and treatments, 19th century, library of Ras Wassan Sagad of Shoa (r. 1808-1813), British Library.

The education system in Ge’ez.

The system of teaching comprises several different stages where students go through a series of specific bēt (‘house’/‘school"). The first was the reading school (nebab bet); followed by the school of music (zema bet) and poetry (qene bet), where students learnt Ge’ez grammar, liturgy (qeddase), and read works such as the 17th century Mäzgäbä Qene (Treasure of Qenes), etc. Those who enroll in the school of music, read from chantbooks (Deggwa) and learn the unique Ethiopian musical notation system known as melekett; after which they continue to the ‘aqwaqwam bēt (school for liturgical dance and musical instruments).

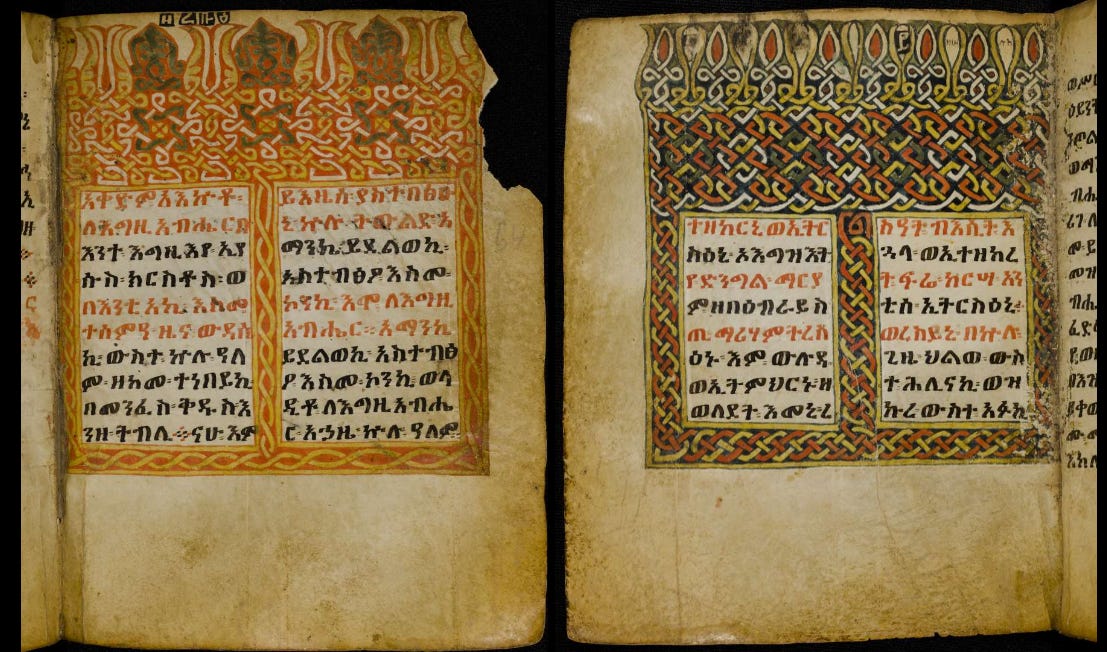

the Deggwa (Hymnbook) and the Qeddase (Liturgy), ca. 1600-1799, Monastery of Dabra Abbey.

19th-century musical manuscript containing school chants. University of Addis Ababa

Students who continue for higher studies go to the ‘school of books’ (mäṣḥaf bet) where they are taught theology, exegesis, commentaries (andemta), using texts such as the liqawent (writings of the Church Fathers), and the mäṣḥeftä mänäkosat (Books of Monks). Other subjects include the calculation of the Ethiopian calendar and its related texts such as the Mäṣḥäfä Abušakǝr (Computus) and the Mäşhafä - Sä'atat (Horologium), as well as Ge'ez calligraphy, manuscript painting and history writing27

the mäṣḥeftä mänäkosat (Books of Monks), 1600-1799, Monastery of Marawe Krestos.

the Mäṣḥäfä Abušakǝr (Computus), 17th century, British Library.

On arrival at the school, which may be a monastery, the home of a scholar, or an outdoor class, the student presents themselves to the master to be accepted as a pupil. The student is then assigned an assistant master or a zärafi (candidate future professor) who gathers other students and is in charge of teaching them and correcting their work. Students made writing ink from charcoal/soot; painting dyes from natural plant material; and used reed pens to write and draw on wooden slates and parchment.28

Teachers likely utilized their personal libraries/collections since the majority of Ge'ez manuscripts were owned and stored by ecclesiastic institutions, and only a fraction of them were available for a limited number of readers. After completing their studies, a period which may take them anywhere between 25 and 50 years, the students receive a certificate that permits them to teach as a däbtära, as well as to serve in churches and schools.29

While some scholars received royal patronage to compose the manuscripts associated with courtly life, the dispersed nature of the intellectual/monastic centers ensured that a significant section of the scholarly community was largely independent of the rulers and at times clashed with them. Notable clashes between the monarchs and the scholars include the 14th-century ideological conflict between Ewosṭatewos (1237-1352) and the clergy that preceded his exile and travel to Armenia, and the 15th-century ideological conflict between the students of Abba Ǝsṭifanos (1397–1444) and the court clergy of King Zärʾa Yaʿəqob.30

The intellectual centers of Ge’ez literature across Ethiopia and Eritrea.

The oldest learning center in the northern horn was the monastery of Däbrä Damo in Tigray, whose establishment dates back to the Aksumite era, and contains material culture of significant antiquity.31 A number of famous monks and abbots were educated at this monastery, such as the 13th-century scholar Iyäsus Mo’a, who later founded the monastery of Däbrä Ḥayq Ǝsṭifanos at Lake Hayq, and Täklä Haymanot (d. 1313), who founded the monastery of Däbrä Libanos.32

Around the same time in what is today Eritrea, several large monasteries and schools were founded in the 14th century. These include Däbrä Bizän, (25 km east of Asmara) which was founded in 1373 by the scholar named Fileppos; and the monastery of Däbrä Demah (or Däbrä Märqorewos, province of Säraye) which was founded by the scholar Märqorewos.33

Monastery of Debre Damo, Ethiopia.

Monastery and monks’ houses at Däbrä Bizän, Eritrea.

The monastery of Däbrä Ḥayq Ǝsṭifanos also a celebrated learning centre where the scholars associated with Iyäsus Mo’a (1214-1293) such as Giyorgis of Sägla, Täkla Haymanot (1214-1313), and Hirutä Amlak pursued their studies. Täkla Haymanot's monastery of Däbrä Libanos, which competed with Däbrä Ḥayq Ǝsṭifanos, was also an important learning center strongly associated with the court, and its abbot received the title of eççägé, which is considered the primate of the Ethiopian monasteries. Two other important monasteries were founded in east Gojjam during this period by the scholars; Särsä Petros at Däbrä Wärq; and Abba Bäkimos at Dima Giyorgis, the latter of whom was formerly a student at Däbrä Libanos.34

Other important centers include the monasteries established by the students of Ewosṭatewos in the regions of Ḥamasen, Säraʾe, and Akkälä Guzay (In Eritrea); the monastery of Gundä Gunde associated with the students of Ǝsṭifanos,35 the monasteries of; Woggera (north of Gondar) which was home to the deggwa scholar aläqa Mesfin; Semada (in the region of Qambember), which was home to the scholar mämher Alämu; Dima Giyorgis and Elyas, known for their teaching of the commentaries, the qene school at Walda attributed to the 15th-century scholar Yohannes Gäblawi, his students; Wäldä Gäbre’el, and Śämrä, and their students; Täwanäy at Gonğ and Dedq Wäldä Maryam at Wadla.36

Some of the most important centers of learning are associated with the royal court. These include; the town of Mahdärä Maryam (Begemder), where a church founded around 1577 by Queen Maryam Sena (wife of Särsä Dengel) became the locus for the teaching of andemta, deggwa and aqwaqwam, with resident scholars such as Abeto Abägaz, known for his historical compilation of 1785–6; and the city of Gondar which became the Ethiopian capital in 1635, under King Fasilädäs, the city also became an intellectual and artistic center, and was renowned for its schools of zema and aqwaqwam, and a unique style of manuscript illumination.37

Chancery and Library of Yohannes I (1667–82) at Gondar, Ethiopia.

Gädlä Wälättä P̣eṭros (Life-Struggles of Walatta-Petros) (b.1593-d.1643) written in 1672-1673 by Galawdewos at Qwarata, Ethiopia.38

Within the royal complex at Gondar, King Yohannes I (1667–82) had a special building constructed for his royal library (see images above), and the city was home to numerous scribes and copyists who preserved older texts, such that even after the Béta Mangest (city treasury) was destroyed by Ras Mika’él in the late 18th century, the Dajazmac Haylu managed to gather several scribes to collect from various monasteries material for a new redaction to replace the lost archives such as books of law and chronicles dating back to the reign of Amda Tseyon.39

Other important scholarly centers associated with royal patronage include; the monastery of Qoma Fasilädäs (south of Begemder) founded in 1620 by Queen Wäld Sä’ala, wife of King Susenyos; the 18th-century monastery of Mota Giyorgis (Eastern Gojam) founded by princess Wälättä Esrael, daughter of Queen Mentewwab; the town of Däbrä Marqos (300 km north-west of Addis Ababa), founded in 1853, and the town of Däbrä Tabor (Begemder) the capital of many rulers of the Oromo dynasty of the Yäggu in the 17th century and later of the emperor Tewodros II (1855–68).40

Church of Dabra Berhān Sellāsē at Gondar, built by Iyasu in 1694

Life and Works of Giyorgis of Sägla (ca. 1364-142541)

Giyorgis of Sägla was one of the best-known Ge’ez scholars of the late Middle Ages, who lived during the reigns of King Dawit II (1380–1413) and King Yǝsḥaq (1414–1430). He was born into a family of court clerics: his father was one of the däbtära attached to the royal court, a function which he would later assume as a tutor to the sons of reigning Kings. Giyorgis was educated in the monastery of Ḥayq Ǝsṭifanos but also visited many monasteries to consult different manuscripts and teachers.42

He was later appointed as nǝburä ǝd (prefect/abbot) of the monastery of Däbrä Dammo during the reign of Dawit, and the two collaborated before they fell out and Giyorgis was imprisoned. He was later released after Dawit’s death and appointed as the head of the community of Abba Bäşälotä-Mika'él in Amhara during the reign of Yǝsḥaq.43

Giyorgis was a prolific writer who is known to have written many original Ge’ez compositions. Atleast seven of his works are extant, such as; the Arganonä Maryam/Weddase (The Organ of Mary) —King Dawit was reportedly so pleased with this text that he had it copied with a special gold ink44; the Mäṣḥäfä Sa'atat (Book of Hours); the Fekkaré Haymanot (Explanation of Faith), and his theological masterpiece, the Mäṣḥafä mǝśṭir (Book of the mystery) in 1424 CE, finished shortly before his death.45

the Arganonä Maryam (The Organ of Mary), ca. 1545-1555, Monastery of Marawe Krestos.

The Mäṣḥafä mǝśṭir is a theological work whose themes underscore the indigeneity of Ge'ez intellectual traditions during a period when external texts were being translated and the doctrines of the church were being debated. Its contents include disputes on the authorship, canonicity, and number of the apostolic books, such as in this section of a passage where Giyorgis reports on a conversation he had with an Armenian priest:

“As for that book (full) of their lies, Peter never uttered it nor did Clement write it down, but it was Yǝsḥaq Tǝgray, a usurper of the episcopate like Melitius. His ordination, too, came from the Melchites. For this reason his teaching is alien to our teaching, and his books, too, to our books, because he brought it from a treasure of lies and translated it with lying words”46

Giyorgis criticizes Yǝsḥaq's literary bias towards the Melchite theology of the Byzantines (which was rejected by the Aksumites and thus by the Tewahedo theologists), preferring instead to rely on older texts such as those contained in the abovementioned Aksumite collection inorder to determine the authenticity of some of the later books being translated into Ge’ez. Giyorgis also discusses several complex dogmatic queries to refute various heretical doctrines and argues for the antiquity of the Tewahedo church, noting that Aksum/Ethiopia embraced Christianity even in the absence of direct apostolic preaching or the martyrdom of believers.47

Giyorgis’ writings were influential not only within the royal court, where they determined the policies of Dawit and Zär'ä Ya'eqob in reconciling the church and the state, but also among his students and successors, as he is known to have founded the monastery of Giyorgis of Gaseçça in Wollo and his works were widely circulated across the kingdom, influencing later generations of scholars and the literary production in Ge’ez.48

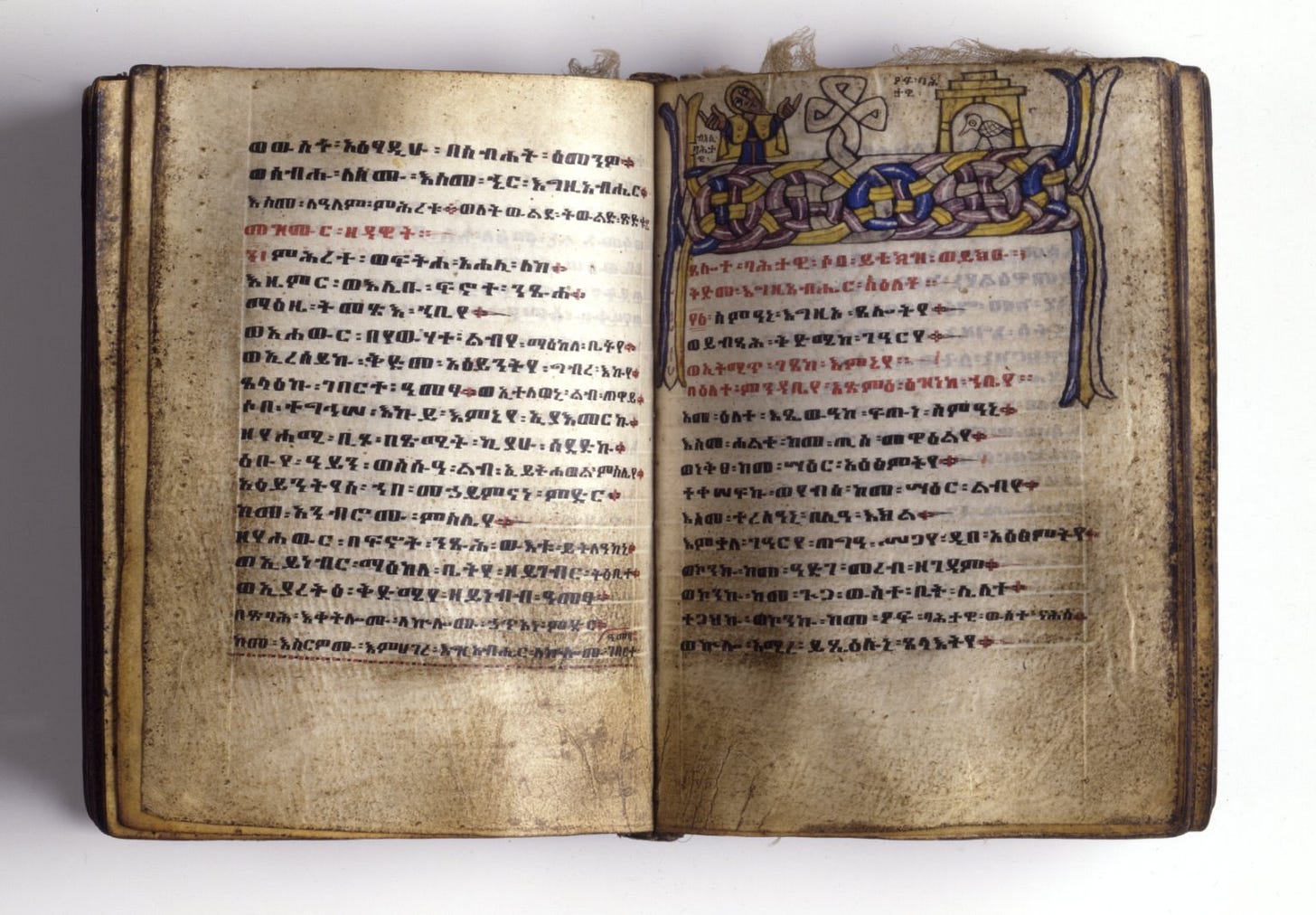

Arganonä Maryam (The Organ of Mary), 17th-century, Met Museum. Written by the scribe Baselyos, the text was illuminated by the ‘ground hornbill painter’ who included a portrait of its original author; Abba Giyorgis of Sägla.

Conclusion.

The above outline of Ge’ez literature is far from exhaustive but should serve as a useful introduction to the rich intellectual history of Ethiopia and Eritrea which spans nearly 2,000 years and contains a complex variety of literary genres and schools, with scholars who played a salient role in the historical processes that shaped the northern Horn of Africa.

Recent projects to digitize and translate the vast corpus of Ge’ez manuscripts carefully preserved in many monasteries and private collections across Ethiopia and Eritrea, such as the Endangered Archives Project49 and ETHIO-SPARE,50 as well as the discoveries of old manuscripts from the Aksumite period, have greatly expanded our understanding of the region’s written traditions and the significance of Ge’ez literature in the intellectual history of Africa.

In antiquity, the armies of the ancient Aksumite empire and the kingdom of Kush used war elephants in ceremonial and military contexts, most famously during the invasion of Mecca by the Aksumite general Abraha.

Please subscribe to read about the war elephants of Aksum and Kush in my latest Patreon article:

The First Millennium BC in the Highlands of Northern Ethiopia and South-Central Eritrea: A Reassessment of Cultural and Political Development by David W. Phillipson pg 265-270

Foundations of an African Civilization: Aksum & the Northern Horn By D. W. Phillipson pg 51-65

The northern Horn of Africa in the first millennium BCE: local traditions and external connections by R. Fattovich pg 13, 26-28, 37.

Foundations of an African Civilization: Aksum & the Northern Horn By D. W. Phillipson pg 53,

The Garima Gospels: Early Illuminated Gospel Books from Ethiopia By Judith S. McKenzie, Francis Watson

The Aksumite Collection or Codex Σ by Alessandro Bausi et al.

The Garima Gospels: Early Illuminated Gospel Books from Ethiopia By Judith S. McKenzie, Francis Watson pg 18

The Zāgwē dynasty (11-13th centuries) and King Yemreḥanna Krestos by Marie-Laure Derat pg 164-165

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 32-33, 35, 38, 285-287

Ethiopian Philosophy, Volume 2 by Claude Sumner pg 119-120

The Traditional Teaching of the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahedo Church By Christine Chaillot pg 90

The Ethiopian Royal Chronicles by Richard Pankhurst pg xii-xvii

The Glorious Victories of 'Āmda S̥eyon, King of Ethiopia by George Wynn Brereton Huntingford pg 13-14, 38-39, 129-134, Studia Aethiopica edited by Verena Böll pg 157-163, 406-412

The Traditional Teaching of the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahedo Church By Christine Chaillot pg 91, A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 228-239)

Ethiopian Philosophy, Volume 2 by Claude Sumner pg 119-120

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 255-256)

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 265-276, 241)

The Traditional Teaching of the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahedo Church By Christine Chaillot pg 93

The Traditional Teaching of the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahedo Church By Christine Chaillot pg 94

The Ethiopian Royal Chronicles by R. Pankhurst pg 70-132

The Traditional Teaching of the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahedo Church By Christine Chaillot pg 94, Coptic and Ethiopic historical writing by Witold Witakowski pg 150

Land and Society in the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia By Donald Crummey, Gondär Land Documents: Multiple Copies, Multiple Recensions by Donald Crummey, Recordmaking, Recordkeeping and Landholding – Chanceries and Archives in Ethiopia (1700–1974) by Habtamu Mengistie Tegegne

The Royal Chronicle of Abyssinia, 1769-1840, Translated by Herbert Weld Blundell.

The Ethiopian Royal Chronicles by R. Pankhurst pg 145-166, Studia Aethiopica edited by Verena Böll pg 153, 247-248)

The Oxford Handbook of Ethiopian Languages edited by Ronny Meyer, Bedilu Wakjira, Zelealem Leyew, pg 65-67. Amharic Sources for Modern Ethiopian History, 1889-1935 by Peter P. Garretson and Richard Pankhurst

Ethiopian Magic Scrolls by Jacques Mercier

The Traditional Teaching of the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahedo Church By Christine Chaillot pg 32-35, 71-77, 95, 115-116)

The Traditional Teaching of the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahedo Church By Christine Chaillot pg 78-79, 115, 119-121, 153-156, A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 291-293

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 319-320, The Traditional Teaching of the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahedo Church By Christine Chaillot pg 32

The Monastic Holy Man and the Christianization of Early Solomonic Ethiopia by Steven Kaplan pg 38-44.

Foundations of an African Civilization: Aksum & the Northern Horn By D. W. Phillipson pg 132, 181

Afrikas Horn by Walter Raunig, Steffen Wenig, pg 154-156

The Traditional Teaching of the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahedo Church By Christine Chaillot pg 141

The Traditional Teaching of the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahedo Church By Christine Chaillot pg 138-139, A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 206-209

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 213-215,

The Traditional Teaching of the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahedo Church By Christine Chaillot pg 133, 80-82

The Traditional Teaching of the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahedo Church By Christine Chaillot pg 140, 133, Major Themes in Ethiopian Painting by Stanislaw Chojnacki pg 489–494.

De la mort à la fabrique du saint dans l’Éthiopie médiévale et moderne by Claire Bosc-Tiessé and Marie-Laure Derat.

The Glorious Victories of 'Āmda S̥eyon, King of Ethiopia by George Wynn Brereton Huntingford pg 26-27

The Traditional Teaching of the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahedo Church By Christine Chaillot pg 138-141

The English Translation of Giyorgis of Saglā’s (Gaśǝč̣č̣a’s) Mäṣḥ afä Mǝśṭir, foreword by Alessandro Bausi, introduction by Abba Hiruie Ermias, pg x

Church and State in Ethiopia: 1270 - 1527 by Taddesse Tamrat pg 222-223

Church and State in Ethiopia: 1270 - 1527 by Taddesse Tamrat pg 223, Notes Towards a History of Ase Dawit I by Steven Kaplan pg 82

Notes Towards a History of Ase Dawit I by Steven Kaplan pg 81

Le domaine des rois éthiopiens, 1270-1527: espace, pouvoir et monarchisme By Marie-Laure Derat, pg 173-206

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 242-243

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 244-250,

Le domaine des rois éthiopiens, 1270-1527: espace, pouvoir et monarchisme By Marie-Laure Derat, pg 173-206, The Traditional Teaching of the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahedo Church By Christine Chaillot pg 139

There is a lot of eurocentric rhetoric here. There is absolutely no evidence that the Kebra Negast was copied from any Arabic or Coptic sources and clearly Ge'ez was not a spoken language until Axum.