TheʿAjamī script of Africa and the Sorabé manuscripts of Madagascar.

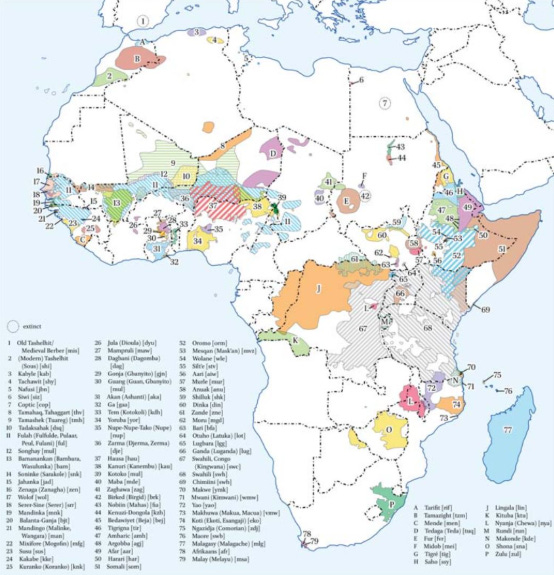

The most widely used writing system in pre-colonial Africa was the ʿAjamī script.1

Following the adoption of the Arabic script in the 10th century, various scholarly communities across the continent began adapting and modifying it to accommodate their own languages, thereby developing distinct orthographic traditions collectively referred to as ʿAjamī (i.e., ‘non-Arab’).2

The gradual shift from Arabic to Ajami was driven by multiple socio-historic and ideological reasons, as African scholars recognized the need to write local language texts that were more accessible to the majority of the population, which was unfamiliar with Arabic grammar.

The documents they produced represent an essential body of knowledge on the history of numerous societies across the continent, encompassing more than seventy languages from Senegal to South Africa.3

This script was utilized in accordance with the uniqueness of each language, since some African languages contained letters and sounds that weren’t found in the Arabic language. Ajami writing was thus used in all intellectual activities, including translations of religious works and classical texts, the composition of original writings on history, law, poetry, and medicine, as well as official correspondence and administrative texts.

In West Africa, the oldest known Ajami writings are found on the epigraphic inscriptions of Gao, in Mali, which are dated to the 11th/12th centuries, and contain Songhay morphological items, titles, and kinship terms.

The oldest extant Ajami manuscripts in West Africa were four Bornu Qur’ans, dated to between the late 16th century and 1669 CE, which were written by local scribes in the Bornu empire. All manuscripts had interlinear vernacular glosses written in ajami, representing Old Kanembu – an archaic variety of the Kanuri language.

Similar bilingual manuscripts written in languages such as Tamashek, Dyula, Wolof, Manding, Fulfulde, and Hausa were first composed between the 16th and 18th centuries, as scholarly networks expanded across West Africa. Ajami literature was further popularized by the reformist movements of the 19th century, resulting in the composition of numerous works in Soninke, Serer, Bamana, Yoruba, Nupe, Akan, and other languages.4

Languages that use the Arabic and Ajami scripts. Map by Meikal Mumin

12th-century funerary stela from Gao-Saney, Musée national du Mali. Commemorative stele for a Queen ‘M.s.r’ dated 1119 CE, and a funerary inscription from Bentiya.

1705 Qur’an with old Kanembu glosses, written by a Kanuri scholar in the Hausa city-state of Katsina, now at the Kaduna National Archives MS.AR33; Old Kanembu manuscript on tawḥīd by Muhammad Suma Lameen, written in 1910.

‘Jante la Kandoolu Kitaaboolu’, a Composite manuscript from the 19th-20th century that includes glosses in Soninke Ajami. Alphousseyni Diante Manuscript Collection, Boston University Libraries.

In East Africa, the earliest Ajami writings appear on the epigraphic inscriptions of Zanzibar and Kilwa (Tanzania), dated to the 12th-14th centuries, which include honorific titles, names, and terms in the Swahili language.

The earliest Ajami manuscripts in East Africa appear during the intellectual renaissance of the 17th century. They include works on poetry, philosophy, law, history, and religion written almost entirely in Swahili, and are attested across a wide region extending from D.R. Congo to Somalia to Mozambique.5

In the northern Horn of Africa, the oldest extant Ajami manuscript was composed in the city of Harar (Ethiopia) during the 16th-17th century by Tayyib al-Wanagi in the Harari language. Ajami works written in Oromo, Amharic, Tigrinya, Somali, and other languages proliferated across the region during the revivalist movements of the 18th and 19th centuries. They included hagiographies, genealogical records, religious texts, and other works of literature.6

Epitaph of Sayyida Aisha bint Mawlana Amir Ali b. Mawlana Sultan Sulayman, c. 1360, Kilwa, Epitaph of ‘Mwana wa Bwana binti mwidani’ , c. 1462, Kilindini, Mombasa.

Folios from the 19th-century Swahili manuscripts; Utenzi wa Herekali, and Utenzi wa Kozi na Ndiwa, SOAS, London.

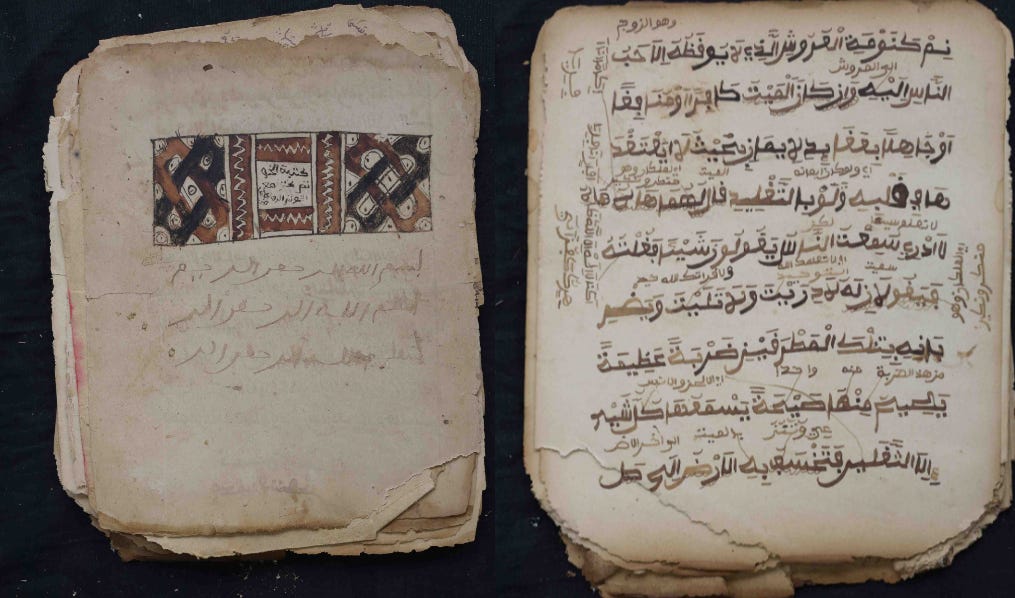

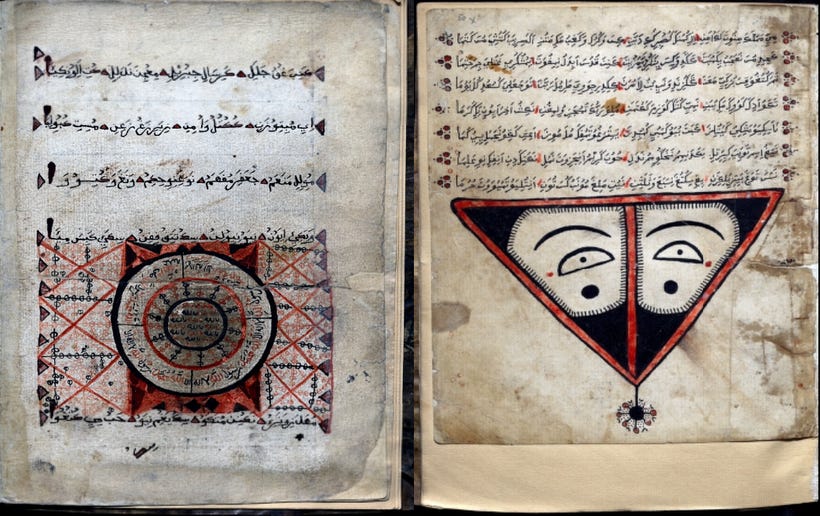

18th-century Harari Manuscript. Addis Ababa University. Institute of Ethiopian Studies. images from HMML Reading Room, Num. IES 00304.

Some of the ʿAjamī literature produced by African scholars has been digitized, with copies available at the African Ajami Library, the Endangered Archives Programme, the Hill and Manuscript Library, and the SOAS library, among other institutions. However, these priceless archives, which reflect the intellectual histories of many African communities, have yet to be translated and studied.7

The rich archival collections of Ajami literature refute the pervasive myth of Africa’s supposed illiteracy that is perpetuated by the overemphasis on African oral traditions in academia and the privileging of external sources over local chronicles.

Ajami sources represent an untapped mine of information for a comprehensive reconstruction of Africa’s past, offering alternative perspectives on historical developments that are mostly known from external sources.

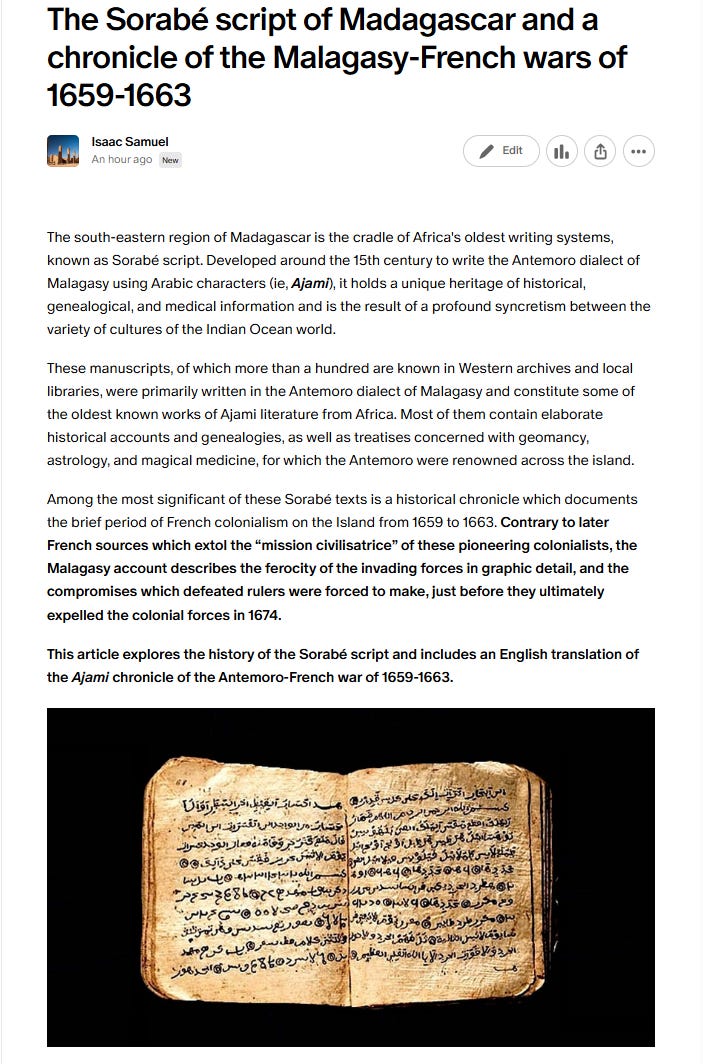

The importance of Ajami literature is evident in the historiography of Madagascar, where the Sorabé script was developed by local scholars in the south-eastern region of the island during the 15th century to write the Antemoro dialect of the Malagasy language.

Manuscripts written in the Sorabé script were some of the oldest known Ajami texts from Africa to appear in Western archives. Many contain elaborate historical accounts and genealogies that reveal the diverse origins of their writers, and the various exploits of their kings and important lineages.

Among these manuscripts was a little-known historical document that chronicles the Malagasy perspective of the brief period of French colonialism on the Island during the 17th century.

Contrary to later imperial sources, which extol the “mission civilisatrice” of these pioneering colonialists, the Malagasy account describes the ferocity of the invading forces in graphic detail, and the compromises that defeated rulers were forced to make before they ultimately expelled the colonial forces in 1674.

The history of the Sorabé script and the 17th-century Malagasy chronicle is the subject of my latest Patreon Article. Please subscribe to read more about it here and support this newsletter:

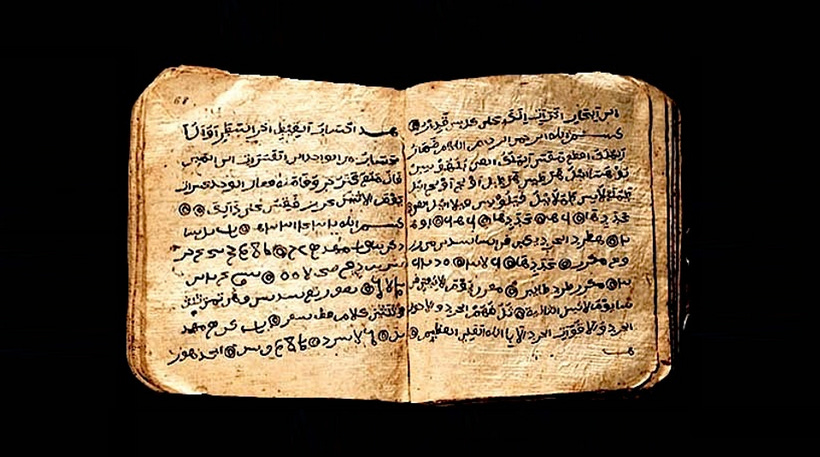

Sorabe manuscript MP 23. Antemoro, Madagascar. 17th century, BNF, Paris.

For other African writing systems, see the Meroitic script (ca. 150 BC), the Ge’ez script of Ethiopia, the Latin script in Kongo and Kahenda, the Nsibidi script (11th-18th century), the Vai script (ca. 1830), and Njoya’s script (1897).

Ajami in Africa: the use of Arabic script in the transcription by Moulaye Hassane. In ‘The Meanings of Timbuktu’ ed. Souleymane Bachir Diagne & Shamil Jeppie, Manuscript Libraries of Sub-Saharan Muslim Africa by Liazzat J. K. Bonate. Muslims Beyond the Arab World: The Odyssey of ʻAjamī and the Murīdiyya By Fallou Ngom

“The Arabic Script in Africa,” by Meikal Mumin in ‘The Arabic Script in Africa: Studies in the Use of a Writing System’ edited by Meikal Mumin, Kees Versteegh

Multiglossia in West African Manuscripts: The Case of Borno, Nigeria by Dmitry Bondarev, Bamana Texts in Arabic Characters: Some Leaves from Mali by Tal Tamari

Manuscript Libraries of Sub-Saharan Muslim Africa by Liazzat J. K. Bonate, pg 488-491

‘Harar’ by Ahmed Zekaria in Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: Volume 2 (2005). Competing and Complementary Writing Systems in the Horn of Africa By Ethan M. Key

From Dust to Digital: Ten Years of the Endangered Archives Programme edited by Maja Kominko

What are all our books doing in European libraries? They came, stole, and then started lying.

Fascinating! But I'm unclear whether this is a *single* script used across various African kingdoms and states, or whether the Ajami refers to a bunch of unrelated scripts developed independently in various places.