The Meroitic script and the documents of ancient Kush (ca. 300BC-450CE)

The Meroitic writing system of the kingdom of Kush is one of the best-known, yet most enigmatic scripts of the ancient world.

Invented around the 3rd century BC by the scribes of Kush, the script was used in everything from Royal chronicles to funerary texts and temple graffiti; a few thousand of which survive to the present day.

While the script itself was deciphered over a century ago, the language behind it has only recently been understood to be part of the group of languages spoken in the eastern Sahel belt of Africa, enabling modern scholars to translate the enigmatic writings of the ancient scribes.

This article outlines the history of the Meroitic script of Kush and includes some of the documents that have been studied.

Map showing the ancient kingdom of Kush.

Sudan’s heritage is currently threatened by the ongoing conflict. Please support Sudanese organizations working to alleviate the humanitarian crisis in the country by Donating to the ‘Khartoum Aid Kitchen’ gofundme page.

A brief background on writing in ancient Kush.

The Meroitic language, which is named after the ancient city of Meroe, was the predominant language spoken in the kingdom of Kush since the end of the 3rd millennium BC. Studies of the list of envoys/delegates from Kerma sent to the Hyksos rulers of Egypt around 1580/1550 BC show that the list includes names that are clearly Proto-Meroitic. These were also similar to the names of the founders of the Napatan kingdom of Kush, who ruled Egypt as the 25th dynasty.1

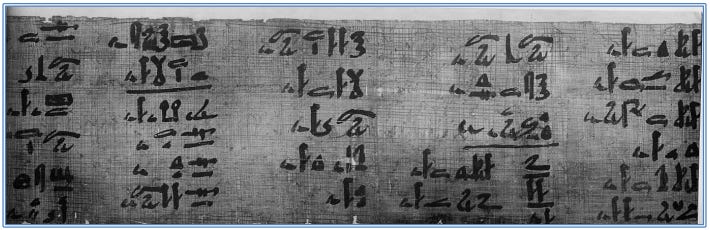

List of foreign names including of Meroitic envoys, on the Papyrus Golenischeff, 15th Dynasty (1640 – 1532 BCE). image by C. Rilly

However, while the language of Kush was Meroitic, the earliest inscriptions from the kingdom were written using Egyptian hieroglyphs, beginning with the inscriptions of King Terereh and Nedjeh of the kingdom of Kerma during the classic period (1650-1550BC).2 After the collapse of Kerma to New Kingdom Egypt and the latter's decline around 1100 BC, the Napatan rulers of Kush re-established the kingdom of Kush and consciously adopted Egyptian writing, as one among many symbols that legitimized their conquest of Egypt in the 8th century BC.

The Napatan kings and scribes of Kush continued to use Egyptian writing until the 4th century, but the quality of their inscriptions was affected by the influence of their main language; Meroitic. When a specific writing system was invented for the Meroitic language in the 3rd century BC, the use of Egyptian for royal inscriptions declined dramatically.3

(left) Inscription of King Terereh of Kerma in the eastern desert region of Sudan at Umm Nabari, ca. 1600-1500BC. Image by Julien Cooper.

(right) monumental inscription of Kush’s king Piye (r. 755BC-714BC, 25th dynasty founder). It shows him receiving the submission of Egyptian chiefs and is considered the longest royal inscription written in Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The Meroitic writings system of Kush.

The earliest form of Meroitic writing was the cursive script which emerged in the early 3rd century BC. The script appeared fully developed by the time the first datable inscription was engraved with Meroitic characters and the name of King Arnekhamani in 220BC. On the other hand, the earliest Meroitic hieroglyphic inscriptions date back to the reign of Taneyidamani (ca. 150 BC), it was likely created by high-ranking scribes during his reign to render into Meroitic the royal documents that were previously written in Egyptian.4

The Meroitic script was thus one of the cultural innovations in Kush that was associated with the emergence of a southern dynasty that overthrew the Napatan dynasty.5 This ‘Meroitic’ dynasty elevated the worship of southern gods like Apedemak and Sebiumeker; established its capital in the extreme south at Meroe with surrounding centers at Naga, and Musawwarat; and formulated a new ideology of power that resulted in the ascendence of several Queen-regnants: the famous Kandakes of Kush.

stele of prince Tedeqene displaying both scripts; Merotic hieroglyphs of the invocation of Osiris and cursive writing for the invocation of Isis6. ca. 200–100 B.C, Beg W, pyramid 19, Meroe, Sudan. Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

The hieroglyphic script of Meroitic didn't directly emerge from the Egyptian hieroglyphs, nor was the cursive Meroitic script similar to that of the Demotic script of late period Egypt. Both the Demotic script and Egyptian hieroglyphs used a mixed system that was partly consonantal and partly logographic, whereas the Meroitic script is an alpha-syllabary with purely phonetic signs. The Meroitic hieroglyphic signs in turn originated from the cursive script based on their phonetic values, and despite resembling Egyptian hieroglyphs, they were written in the opposite direction.7

Importantly, unlike in Egypt where the hieroglyphic script was used for royal and temple texts while cursive was for administration and other non-royal use, this sharp dividing line didn't exist for Meroitic scripts where all monumental royal inscriptions were written in cursive from the onset.

According to the Nubiologist László Török, the use of the cursive script “reveals that the creation of Meoritic literacy was motivated by the necessity of an easily accessible monumental royal communication and display. Evidently, this monumental communication had to be in a language that was spoken and understood by the particular group of the population to which the communication was primarily addressed… i.e., the particular elite from which also the new dynasty itself must have originated.”8

The Meroitic writing system is an alphasyllabary similar to the Ge'ez script of Ethiopia and Eritrea and the Indian scripts like Brahmi and Devanagari.9

The Meroitic script comprised only signs with phonetic values, 23 in each set, cursive and hieroglyphic. The cursive script is written from right to left, while the hieroglyphic script can be written in both directions. Each basic sign represented a syllable including a consonant plus inherent vowel /a/. For instance, 𐦲 in cursive, 𓅭 in the hieroglyphic script was read /ka/, even though it is traditionally transliterated k in the Latin script (because it was initially thought to be an alphabetical script). An example of this is a word like 𐦫𐦳𐦧 for “prince”10 that is transliterated as ‘pqr’ and not ‘pa-qa-ra’, which would be closer to the actual pronunciation.11

Meroitic signs and numerals. image by C. Rilly.

Meroitic documents and translation: the funerary texts.

Approximately 2,000 Meroitic texts have been found so far in excavations and surveys conducted in Sudan and in Egyptian Nubia, from which 1,600 have been published. About half of the written documents are funerary texts, at least 24 of them are royal chronicles, and the rest are ostracon on potsherds, graffiti engraved on temple walls, and a handful of papyrus writings. They are all classified with a number in the Répertoire d’Épigraphie Méroïtique, or REM.12

While the vast majority of the extant writings were inscribed on stone, this is only due to the durability of stone. The form of cursive signs used in Meroitic writing, with their curves and long tails for signs that are very similar (eg Hha 𐦮, Sa 𐦯, and Ka 𐦲) show that they were chiefly traced with ink on papyrus paper and potsherds. The papyrus documents were, however, too fragile to survive Sudan's climate, and only a few have so far been recovered, primarily from Qsar Ibrim in Lower Nubia.13

The Meroitic language is only superficially known, although both scripts were deciphered about a century ago by the archeologist Francis Llewellyn Griffith.14 This is mostly due to a lack of 'bilingual texts' (in Meroitic and a better-known language) as well as the erroneous claim by earlier scholars that Meroitic was isolated from other African languages (hence no comparable translations).15

However recent research, primarily by the linguist Claude Rilly, has shown that Meroitic is part of a linguistic family known as ‘Nilo-Saharan’, a very broad family which includes languages like Maasai of Kenya and the Toubou of Chad. Within this family are the "Northern Eastern Sudanic" languages to which Meroitic belongs, as well as; the Nubian languages of Sudan; the Nara languages of Eritrea16; the Taman languages in Chad/Sudan; and the Nyima group of Suda’s Nuba Mountains. Comparing these languages enables linguists to reconstruct a common ancestor, proto-Northern Eastern Sudanic, whose proximity to Meroitic is often impressive, and has thus enabled the translation of some of the texts.17

The first of these are the funerary texts, which follow a standard formula and are thus relatively easy to compare; invocation to Isis and Osiris, name of the deceased and their parents, official titles of the deceased and of their most famous relatives, final benedictions requiring the gods to provide water, bread, and a good meal to them. These stereotyped formulae and the great number of texts explain why they are the best-understood Meroitic documents. Meroitic funerary inscriptions can be divided into two broad categories; those made for the members of the royal family and those written for members of the non-royal elite. 18

Funerary stela with Meroitic inscriptions and a painting of a Meroitic lady and her son, ca. 100-200 CE, Karanog, Nubia, Cairo Museum JE40229. Painted funerary stela with Meroitic inscriptions and a male figure. 1st-3rd century CE. Karanog, Nubia. Penn Museum.

Funerary stele with Meroitic inscriptions, ca. 1st cent. BC-3rd century CE. Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and Penn Museum.

Funerary stelai of the Lady Ataqelula and Lady Maliwarase, ca. 3rd century CE, Sedeinga, Sudan. images by C. Rilly.

In the last two stelai shown above, the lady Ataqelula was the daughter of a priest from Pnubs (Kerma), her ancestral lineage included a royal prince (pqr qorise), a first prophet of Amun (womnise-lh) and a female temple musician (wrtxn). One of her brothers was an ateqi-priest, attached to the Isis center at Sedeinga and another brother was a ‘great of Horus’ (lh Ar-se-l).

Lady Maliwarase was a daughter of ‘a high governor’ (xrpxne lx-li), her maternal uncle was an ateqi-priest, connected to the Isis center in Sedeinga. Two of her brothers were ‘two high priests in Primis’ (either Qasr Ibrim or Amara). Her son was a priest of Masha, god of the Sun (ate Ms-o) and another son was ‘governor of Faras’ (xrpxene Phrse-te-l). These inscriptions reveal the close links between the elites of Sedeinga and indicate that the rest of the kingdom as far north as Kerma and Faras were administered by closely related elites. 10

Among the funerary texts were also offering tables, upon which food and drink offerings were placed for sustaining the afterlife. The Meroites reshaped the meaning, decoration, and texts on offering tables by combining them with indigenous elements to create an expression of their own beliefs and practices. Decorations and writings on such offering tables, recorded and magically re-created an actual offering rite. These showed Anubis and a companion goddess like Nephthys making offerings resembling real rites conducted at the burial by mask-wearing priests, and were unparalleled in Egypt or the Napata period.19

Offering table of Prince Tedeken, ca. 200–100 B.C.Beg W, pyramid 19, Meroe. Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Offering table of King Amanitaraquide, ca. 40–50 CE. N 16, Meroe. Sudan. Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Offering tables with inscriptions in cursive Meroitic, ca. 270 BC– 320 CE, Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Meroitic documents: the Royal Chronicles.

The longest royal chronicle (REM 1044) measures 1.60 meters in height and 161 lines of text on the four sides of the stone surface engraved by King Taneyidamani and erected at the temple of Jebel Barkal. Other well-known Meroitic royal chronicles include the great stelae of Prince Akinidad and the Candace (ruling queen) Amanirenas (REM 1003), the stele of the Candace Amanishakheto (REM 1041/1361), and the late inscription of the Blemmyan king Kharamadoye (REM 0094).20

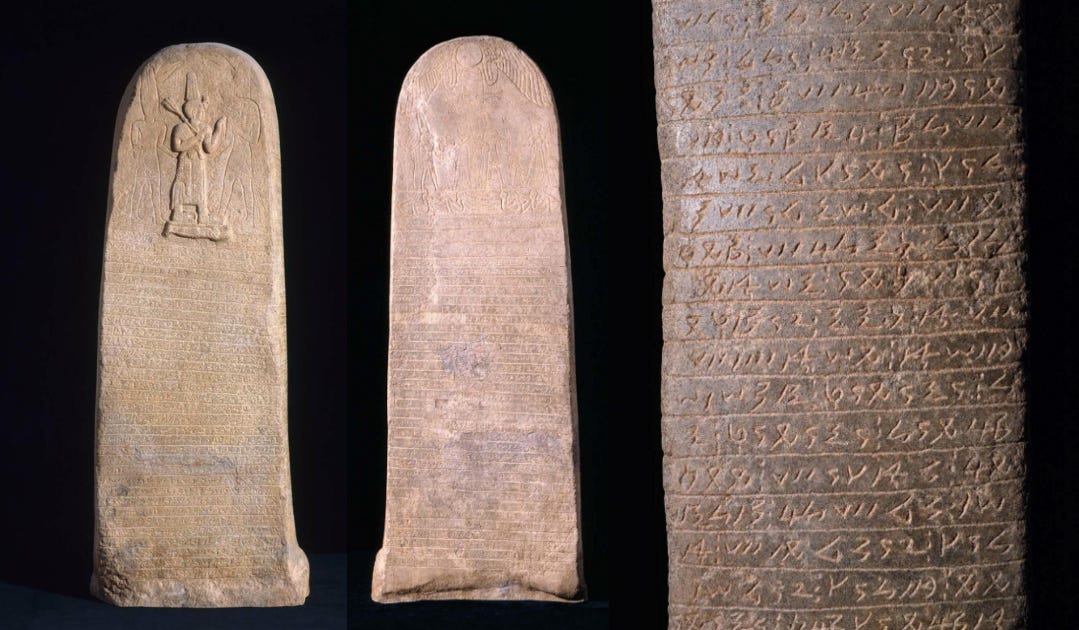

Victory stele of King Tanyidemani with Meroitic inscription on both faces and edge. ca. 180–140 B.C, Gebel Barkal, Sudan. Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Royal stela of Queen Amanirenas and King Akinidad, ca. 1st century BC, Hamdab, Sudan. British Museum.

Stele fragments (possibly royal) with cursive Meroitic inscriptions, one showing bound captives. ca. 270BC-320CE, Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

(L-R) Stela of Queen Amanishakheto from the Temple of Amun at Naga, late 1st century BC; Detail of the second stele of Hamadab (REM 1039) of Candace Amanirenas and Prince Akinidad, early 1st century CE; Detail of the Naga stele of Queen Amanishakheto showing a bound Roman captive with the ethnic label of ‘Tameya’. last two images by C.Rilly.

The royal chronicles begin with a protocol that gives the royal names and titles, and they continue mostly with what appear to be religious phrases followed by reports of military campaigns. The texts of the Royal Chronicles and Decrees contain a richer vocabulary and morphology than the funerary texts, they are thus only partially understood with only a few lines having been translated by studying recurring phrases.21

Among the few that have attracted significant interest are the two stela from Hamadab that were commissioned by Queen Amanirenas (famous for her defeat of Rome), and the stele of her sucessor; Queen Amanishakheto.

These were primarily studied in order to find a Meroitic version of the Roman invasion of Kush that was described by Strabo’s account, regarding an invasion that only managed to sack Kush’s former capital: Napata. While most of the text remains untranslated, the recurrence of words relating to warfare (eg: raiding, taking booty, captives, etc), locations (like Napata), and the ethnonym Tameya indicates that the second stela of Hamadab describes a war with the ‘Tameya,’ the latter of whom also appear in later Meroitic accounts as a generic ethnonym for Romans in Egypt (see Kharamadoye’s inscription below). They are thus presented at the top of the stela, with the inscription: “These are the Tameya captives.” 22

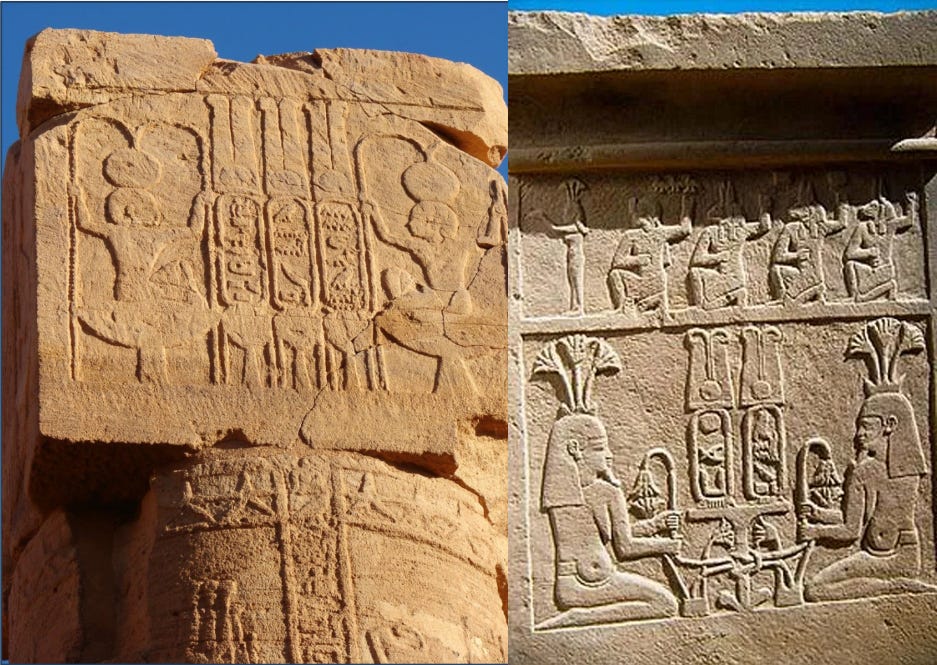

Related to these are the official inscriptions written in hieroglyphic script, often accompanying the figures of gods and rulers. The hieroglyphs were a sacred script, reserved for ceremony and royalty, that possessed impressive magical value and was subject to taboos. The majority of these are found at the temples of Naga, such as the lion temple and the temple of Amun, which are better preserved than the other Meroitic sites.23

Meroitic hieroglyphic inscriptions on a column and a sanctuary altar from the Amun Temple at Naga, mentioning King Natakamani and Queen Amanitore. 1st century CE. Images by C. Rilly, and Muzeum Archeologiczne w Poznaniu.

Hundreds of Meroitic graffiti engraved by pilgrims on the walls of the temples at Philae, Kawa, Musawwarat, etc. have been found, and some partially translated based on comparisons with similar inscriptions made on the same temples in Greek and Demotic.24

Other Meroitic writings include; ostraca recording administrative accounts; commemorations of funerary offerings, spells against enemy leaders to be ritually vanquished; and protective amulets. A numerical ostracon from Qasr Ibrim indicates that the highest number of Meroitic numerals was 900,000. The ostracon was likely an exercise for students, it gives for each rank (fractions, units, tens, etc.) a variable number of instances (from five to ten). The fractions were represented by sets of dots resembling pips on dice, their system was not decimal, but duodecimal (like inches in the Imperial system).25

Sheath for a staff with Meroitic inscriptions, ca. 110–90 BC, Gebel Barkal, Sudan. Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Copper-alloy ritual figure of bound captive, with meroitic inscriptions. ca. 1st century CE, Meroe, Sudan. British Museum. the inscription reads: qo : qore nobo-l-o “this one, it is the Nubian (Noba) king.”26

Ostracon inscribed with Meroitic characters, ca. 100BC-300CE, Karanog and Qasr Ibrim, Lower Nubia. Penn Museum, and British Museum.

Pilgrim’s feet and Meroitic inscription from the Temple of Isis at Philae. image by C. Rilly

Image of graffiti on the wall of site 964. on the left is are two astronomers using an instrument while on the right are astronomical observations of equations written with Meroitic numerals. University of Liverpool. Read more about the Meroe observatory here:

The Meroitic script after the fall of Kush. ca. 360-452 CE

The Meroitic kingdom of Kush collapsed not long after its invasion by King Ousanas of Aksum in the first half of the 4th century CE. The last inscription among the known Meroitic rulers was commissioned by King Talakhideamani (reign: late 3rd century to early 4th century CE), at the Amun Temple complex in Meroe, the temple of Musawwarat, and in the Meroitic chamber at Philae (in Roman Egypt) where he sent his envoys, and where previous generations of Kush’s envoys to Rome had left many inscriptions. 27

(left) a Meroitic Delegation and their corresponding inscriptions depicted in the Temple of Isis at Philae (right). Detail of an offering table likely made by a Meroitic ambassador to Rome, (REM 0129) from Faras, Lower Nubia. British Museum. The words ‘apote’ and ‘Arome’ (ie: envoy to Rome) appear together in line 4. images and captions by Jeremy Pope. For more on Nubians in Rome, see: ‘Africans in Rome and Romans in Africa.’

Meroitic hieroglyphic inscription on a bronze bowl from el-Hobagi. image by C. Rilly.

The Meroitic script survived only a few decades after the collapse of the kingdom, some of the post-Meroitic inscriptions were made within the former kingdom’s heartland, but most were from the region of lower Nubia (what is today southern Egypt) where non-Meroitic elites, such as the Noba and the Blemmyes, had in the early 4th century competed with Kush for control of the region.28

For example, the last known Meroitic hieroglyphic inscription (REM 1222) was engraved on a bronze bowl found in a burial mound at el-Hobagi (just south of Meroe) dated 350CE that was made for a ruler of the Noba, and the last royal inscription in cursive is a wall inscription commissioned by of the Blemmyan king Kharamadoye in the temple of Kalabsha (REM 0094), dated to ca. 420 CE.29

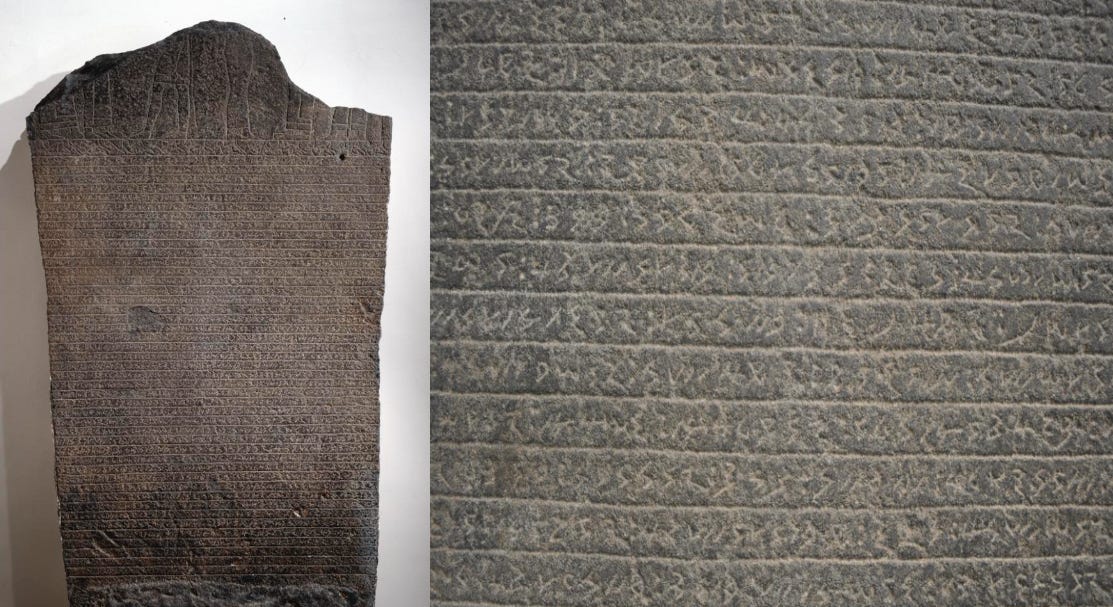

Meroitic inscription of the Blemmyan king Kharamadoye in the temple of Kalabsha, lower Nubia. 4th century CE.

The above inscription remains mostly incomprehensible, despite several attempts by multiple scholars, as only a few words have been translated. It identifies the qore (King) Kharamadoye who commissioned it, and includes the name of a qore lh (great king) named Yisemeniye, who appears as Isemne in his own Greek inscription from the same temple. These two kings were both Blemmeyan rulers, who took over the region of lower Nubia from the Meroites and the Noubades (Nubians), before the last group ultimately defeated them. The text also mentions qore 8 hre-se (eight kings of the north) between Philae and Adere, who, like Kharamadoye, may have been subordinate to the ‘Great King’ Isemne (earlier interpretations suggested they were rivals). The rest of the text likely deals with the distribution of the territory of Lower Nubia at the end of several military campaigns, and mentions the Mẖo (Makhu/Magi =Noubades) and the Temey (ie: Romans, see the translation of the royal chronicles mentioned above).30

According to the linguist Claude Rilly, this text was written by a scribe familiar with Meroitic royal inscriptions as it follows older models. He argues that “it is quite likely that the choice of the old language of Kush, in preference to Greek, the lingua franca of the Eastern Roman Empire and adjacent countries, stems from a desire to present the Blemmye domination over Kalabcha as a continuation of the defunct kingdom of Meroe to a local population that must still have been mostly composed of Meroites. But we do not know what weight the latter, who were no longer masters of their destiny, could have had in the rivalry that opposed the new lords of Nubia, Blemmyes and Nubades.”31

The very last Meroitic texts were a few lines of graffiti engraved in the temple at Philae by the Isis priests of the Smet family (in Meroitic: Semeti), who also left in the same place the last Demotic inscription, dated to 452 CE.32 This temple was the last bastion of the Isiac religion that once spread over the ancient Roman world but was gradually displaced by Christianity, which was adopted by the Noubadian/Noba/Nubian kings who founded the Medieval Nubian Kingdoms.

These final inscriptions formally mark the end of Meroitic writing, as the Nubian rulers who succeeded them devised their own script, but retained only three signs from Meroitic cursive.33

In this way, a small part of the ancient Meroitic script survived through the Middle Ages until the eventual collapse of Medieval Nubia in the 15th century.

At the height of Rome in the first century of the common era, the Egyptian goddess Isis became one of the most popular deities across the empire, thanks in part to the activities of Nubian missionaries who are attested as far as Herculaneum in Italy. The worship of Isis was thus the most widely practiced religion originating from the African continent.

Please subscribe to read about the Nubian priests of Isis in the ancient Roman world:

nnn

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia edited by Geoff Emberling, Bruce Williams pg 300, 655-656, The Meroitic Language and Writing System By Claude Rilly, Alex de Voogt pg 5-6, 177-179)

Kushites expressing 'Egyptian' kingship: Nubian dynasties in hieroglyphic texts and a phantom Kushite king by Julien Cooper pg 144, Between Two Worlds: The Frontier Region Between Ancient Nubia and Egypt By László Török pg 103-106

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia edited by Geoff Emberling, Bruce Williams pg 654

Rilly, Claude, 2022, Meroitic Writing. In Andréas Stauder and Willeke Wendrich (eds.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, pg 5

The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization By László Török pg 420-424, Hellenizing Art in Ancient Nubia 300 B.C. - AD 250 and Its Egyptian Models ... By László Török pg 13-21, 209-213.

The Meroitic Language and Writing System By Claude Rilly, Alex de Voogt pg 11

The Meroitic Language and Writing System By Claude Rilly, Alex de Voogt pg 7-9, The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia edited by Geoff Emberling, Bruce Williams pg 662

Between Two Worlds: The Frontier Region Between Ancient Nubia and Egypt, 3700 BC-AD 500 by László Török pg 415-417

For this last comparison, see: The Meroitic Script and the Understanding of alpha-syllabic writing by Alexander J. de Voogt

These Meroitic signs are actually arranged in reverse, but substack won’t let me post them that way for some reason

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia edited by Geoff Emberling, Bruce Williams pg 663, Rilly, Claude, 2022, Meroitic Writing. In Andréas Stauder and Willeke Wendrich (eds.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, pg 8-9. for other studies of Meroitic signs, see: A phonological investigation into the Meroitic ‘syllable’ signs – ne and se and their implications on the e sign* by Kirsty Rowan (SOAS)

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia edited by Geoff Emberling, Bruce Williams pg 665, The Meroitic Language and Writing System By Claude Rilly, Alex de Voogt pg 10

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia edited by Geoff Emberling, Bruce Williams pg 665

Karanòg : the Meroitic inscriptions of Shablul and Karanòg by Francis Llewellyn Griffith.

Recent Research on Meroitic, the Ancient Language of Sudan by Claude Rilly pg 14

for this specific comparison between Nara and Meroitic, see: The possible link between Meroitic and Nara by by G Ferrandino

Recent Research on Meroitic, the Ancient Language of Sudan by Claude Rilly 15-23

The Meroitic Language and Writing System By Claude Rilly, Alex de Voogt pg 11-30

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia edited by Geoff Emberling, Bruce Williams pg 634-635.

The Meroitic Language and Writing System By Claude Rilly, Alex de Voogt pg 30

The Meroitic Language and Writing System By Claude Rilly, Alex de Voogt pg 31-33

The Meroitic Language and Writing System By Claude Rilly, Alex de Voogt pg 51

The Meroitic Language and Writing System By Claude Rilly, Alex de Voogt pg 33-34

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia edited by Geoff Emberling, Bruce Williams pg 664

'Enemy Brothers. Kinship and Relationship between Meroites and Nubians (Noba)' by Claude Rilly, pg 216.

‘Appendix: New Light on the Royal Lineage in the Last Decades of the Meroitic Kingdom’ in : The Amun Temple at Meroe Revisited by Krzysztof Grzymski pg 144-146

Between Two Worlds: The Frontier Region Between Ancient Nubia and Egypt, 3700 BC-AD 500 by László Török pg 469-473.

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia edited by Geoff Emberling, Bruce Williams pg 664)

Batailles sur les ruines de Méroé by Claude Rilly, pg 384

Batailles sur les ruines de Méroé by Claude Rilly, pg 385

Batailles sur les ruines de Méroé by Claude Rilly, pg 392

Rilly, Claude, 2022, Meroitic Writing. In Andréas Stauder and Willeke Wendrich (eds.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, pg 7

amazing stuff. thank you! i look forward to your next piece. I love learning about new things.

Happy New Yrs to all when it comes, and I must say this is a wonderful article , I'm waiting for when they gave a full translation of the Merotic side of the peace treaty with the Romans, hopefully A.I can help make this possible.