The General History of Africa

a comprehensive look at states and societies across the continent's entire history.

African historiography has come a long way since the old days of colonial adventure writing.

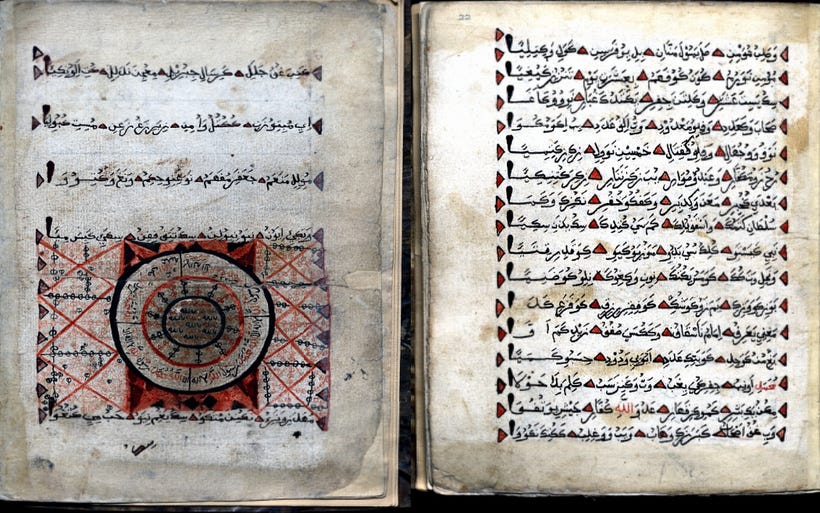

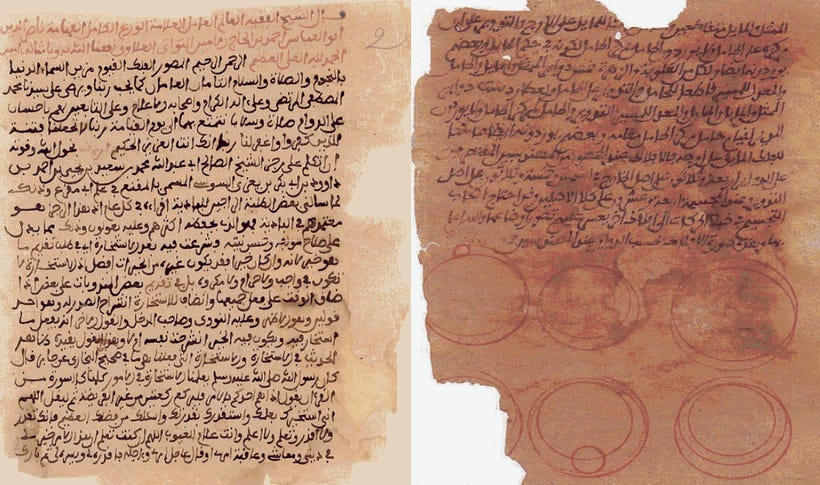

Following the re-discovery of countless manuscripts and inscriptions across most parts of the continent, many of which have been digitized and several of which have been studied, including documents from central Africa, and lesser-known documents such as those written in the Bamum script, the Vai script, and Nsibidi;

We are now sufficiently informed on how Africans wrote their own history, and can combine these historical documents with the developments in African archeology and linguistics, to discredit the willful ignorance of Hegelian thinking and Eurocentrism.

This article outlines a general history of Africa. It utilizes hundreds of case studies of African states and societies from nearly every part of the continent that I have previously covered in about two hundred articles over the last three years, inorder to paint a more complete picture of the entire continent’s past.

[click on the links for sources]

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by joining our Patreon community, and help keep this newsletter free for all:

Africa from the ancient times to the classical era.

Chronologically, the story of Africa's first complex societies begins in the Nile valley (see map below) where multiple Neolithic societies emerged between Khartoum and Cairo as part of a fairly uniform cultural spectrum which in the 3rd millennium BC produced the earliest complex societies such as the Egyptian Old Kingdom, the Nubian A-Group culture and the kingdom of Kerma.

At its height in 1650 BC, the kings who resided in the capital of Kerma controlled a vast swathe of territory that is described as “the largest political entity in Africa at the time." The rulers of Kerma also forged military and commercial alliances with the civilization of Punt, which archeologists have recently located in the neolithic societies of the northern Horn of Africa.

In West Africa, the neolithic culture of Dhar Tichitt emerged at the end of the 3rd millennium BC as Africa’s oldest complex society outside the Nile valley, and would lay the foundations for the rise of the Ghana empire. To its south were groups of semi-sedentary populations that constructed the megalith complex of the Senegambia beginning around 1350 BC.

The central region of west Africa in modern Nigeria was home to the Nok neolithic society which emerged around 1500 BC and is renowned for its vast corpus of terracotta artworks, as well as some of the oldest evidence for the independent invention of iron smelting in Africa.

In the Lake Chad basin, the Gajigana Neolithic complex emerged around 1800BC in a landscape characterized by large and nucleated fortified settlements, the biggest of which was the town of Zilum which was initially thought to have had contacts with the Garamantes of Libya and perhaps the aethiopian auxiliaries of Carthage that invaded Sicily and Roman Italy.

Africa’s oldest Neolithic cultures as well as sites with early archaeobotanical evidence for the spread of major African crops. Map by Dorian Fuller & Elisabeth Hildebrand.

In the Nile valley, the geographic and cultural proximity between Nubia and Egypt facilitated population movements, with Nubian mercenaries and priestesses settling in Naqada, Hierakonpolis, and Luxor, all of whom were later joined Nubian elites from Kush who settled in Thebes, Abydos, and Memphis.

By the 8th century BC, the rulers of Kush expanded their control into Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean and left a remarkable legacy in many ancient societies from the ancient Assyrians, Hebrews, and Greeks who referred to them as 'blameless aethiopians.'

After Kush's withdrawal from Egypt, the kingdom continued to flourish and eventually established its capital at Meroe, which became one of the largest cities of the ancient world, appearing in various classical texts as the political center of the Candances (Queens) of Kush, and the birthplace of one of Africa's oldest writing systems; the Meroitic script.

The Meroitic kingdom of Kush constructed the world's largest number of pyramids, which were a product of Nubian mortuary architecture as it evolved since the Kerma period, and are attested across various Meroitic towns and cities in both royal and non-royal cemeteries.

The kingdom of Kush initiated and maintained diplomatic relations with Rome after successfully repelling a Roman invasion, thus beginning an extensive period of Africa's discovery of Europe in which African travelers from Kush, Nubia, Aksum, and the Ghana empire visited many parts of southern Europe.

To the east of Kush was the Aksumite empire, which occupied an important place in the history of late antiquity when Aksum was regarded as one of the four great kingdoms of the world due to its control of the lucrative trade between Rome and India, and its formidable armies which conquered parts of Arabia, Yemen and the kingdom of Kush.

Aksum's control over much of Arabia and Yemen a century before the emergence of Islam created the largest African state outside the continent, ruled by the illustrious king Abraha who organized what is arguably the first international diplomatic conference with delegates from Rome, Persia, Aksum and their Arab vassals.

Queen Shanakadakheto’s pyramid, Beg. N 11, 1st century CE, Meroe, Sudan.

The African Middle Ages (500-1500 CE)

After the fall of Kush in the 4th century, the Nubian kingdom of Noubadia emerged in Lower Nubia and was powerful enough to inflict a major defeat on the invading Arab armies which had seized control of Egypt and expelled the Byzantines in the 7th century.

Noubadia later merged with its southern neighbor, the Nubian kingdom of Makuria, and both armies defeated another Arab invasion in 651. The kings of Makuria then undertook a series of campaigns that extended their control into southern Egypt and planned an alliance with the Crusaders.

The Arab ascendance in the Magreb expanded the pre-existing patterns of trade and travel in the central Sahara, such that West African auxiliaries participated in the Muslim expansion into southern Europe and the establishment of the kingdom of Bari in Italy.

By the 12th century, oasis towns such as Djado, Bilma, and Gasabi emerged in the central Saharan region of Kawar that were engaged in localized trade with the southern kingdom of Kanem which eventually conquered them.

The empire of Kanem then expanded into the Fezzan region of central Libya, creating one of Africa's largest polities in the Middle Ages, extending southwards as far as the Kotoko city-states of the Lake Chad basin, and eastwards to the western border of the kingdom of Makuria.

ruins of Djado in the Kawar Oasis of Niger.

At its height between the 10th to 13th centuries, the kingdom of Makuria established ties with the Zagwe kingdom of Ethiopia, facilitating the movement of pilgrims and religious elites between the two regions. The Zagwe kingdom emerged in the 11th century after the decline of Aksum and is best known for its iconic rock-cut churches of Lalibela.

East of the Zagwe kingdom was the sultanate of Dahlak in the red sea islands of Eritrea whose 'Abyssinian' rulers ruled parts of Yemen for over a century. The Zagwe kingdom later fell to the ‘Solomonids’ of Ethiopia in the late 13th century who inherited the antagonist relationship between the Christian and Muslim states of North-East Africa, with one Ethiopian king sending a warning to the Egyptian sultan that; "I will take from Egypt the floodwaters of the Nile, so that you and your people will perish by the sword, hunger and thirst at the same time."

African Christian pilgrims from Nubia and Ethiopia regularly traveled to the pilgrimage cities in Palestine, especially in Jerusalem, where some eventually resided, while others also visited the Byzantine capital Constantinople and the Cilician kingdom of Armenia.

Church of Beta Giyorgis in Lalibela

In the same period, west African pilgrims, scholars, and merchants also began to travel to the holy lands, particularly the cities of Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem, often after a temporary stay in Egypt where West African rulers such as the kings of Kanem had secured for them hostels as early as the 13th century.

In many cases, these West African pilgrims were also accompanied by their kings who used the royal pilgrimage as a legitimating device and a conduit for facilitating cultural and intellectual exchanges, with the best documented royal pilgrimage being made by Mansa Musa of Mali and his entourage in 1324.

The empire of Mali is arguably the best-known West African state of the Middle Ages, thanks not just to the famous pilgrimage of Mansa Musa, but also to one of its rulers’ daring pre-Colombian voyage into the Atlantic, as well as Mali’s political and cultural influence on the neighboring societies.

To the East of Mali in what is today northern Nigeria were the Hausa city-states, which emerged in the early 2nd millennium. Most notable among these were the cities of Kano, Katsina, Zaria, and Gobir, whose merchants and diasporic communities across West Africa significantly contributed to the region's cultural landscape, and the external knowledge about the Hausalands.

In the distant south-east of Mali in what is today southern Nigeria was the kingdom of Ife, which was famous for its naturalistic sculptural art, its religious primacy over the Yorubaland region of southern Nigeria, and its status as one of the earliest non-Muslim societies in west Africa to appear in external accounts of the middle ages, thanks to its interactions with the Mali empire that included the trade in glass manufactured at Ife.

Crowned heads of bronze and terracotta, ca. 12th-15th century, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

The sculptural art of Ife had its antecedents in the enigmatic kingdom of Nri, which flourished in the 9th century and produced a remarkable corpus of sophisticated life-size bronze sculptures in naturalistic style found at Igbo-Ukwu. The sculptural art tradition of the region would attain its height under the Benin kingdom whose artist guilds created some of Africa's best-known artworks, including a large collection of brass plaques that adorned the palaces of Benin's kings during the 16th century.

In the immediate periphery of Mali to its west were the old Soninke towns of Tichitt, Walata, and Wadan, some of which were under the control of Mali’s rulers. On the empire’s southern border was the kingdom of Gonja whose rulers claimed to be descended from the royalty of Mali and influenced the spread of the distinctive architecture found in the Volta basin region of modern Ghana and Ivory Coast. Straddling Mali’s eastern border was the Bandiagara escarpments of the Dogon, whose ancient and diverse societies were within the political and cultural orbit of Mali and its successors like Songhai.

Ruins of Wadan, South eastern Mauritania

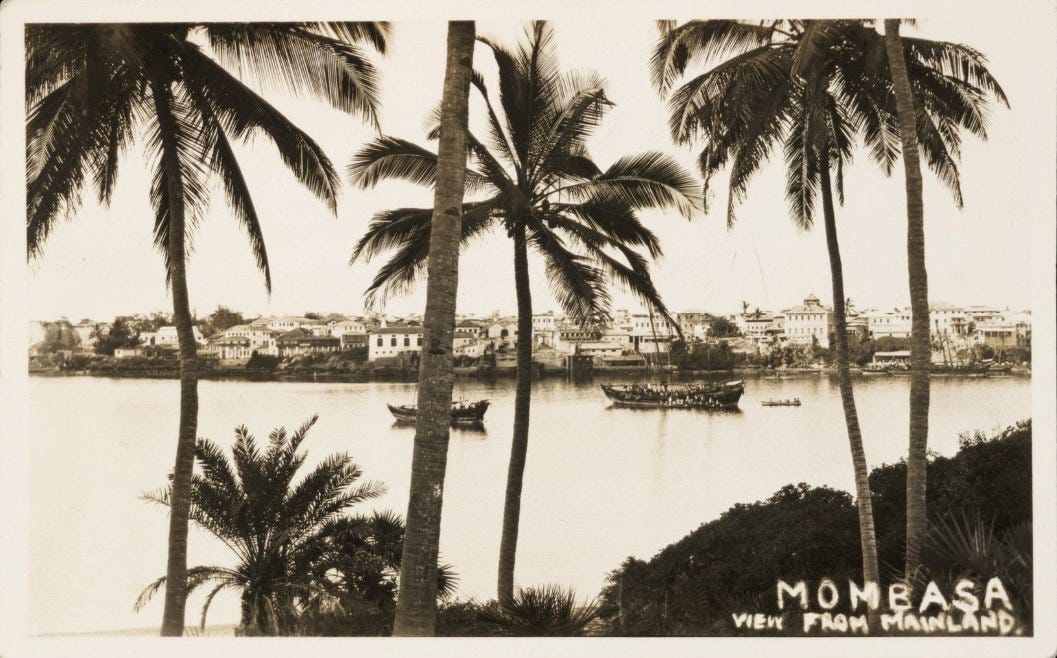

On the eastern side of the continent, a long chain of city-states emerged along the coastal regions during the late 1st millennium of the common era that were largely populated by diverse groups of Bantu-speakers such as the Swahili and Comorians. Cosmopolitan cities like Shanga, Kilwa, Mombasa, and Malindi mediated exchanges between the mainland and the Indian Ocean world, including the migration and acculturation of different groups of people across the region.

The early development of a dynamic maritime culture on the East African coast enabled further expansion into the offshore islands such as the Comoro archipelago where similar developments occurred. This expansion continued further south into Madagascar, where city-states like Mahilika and Mazlagem were established by the Antalaotra-Swahili along its northern coastline.

The movement of people and exchanges of goods along the East African coast was enabled by the sea-fairing traditions of East African societies which date back to antiquity, beginning with the Aksumite merchants, and peaking with the Swahili whose mtepe ships carried gold and other commodities as far as India and Malaysia.

The gold which enriched the Swahili city-states was obtained from the kingdoms of south-eastern Arica which developed around monumental dry-stone capitals such as Great Zimbabwe, and hundreds of similar sites across the region that emerged as early as the 9th century. One of the largest of the Zimbabwe-style capitals was the city of Khami, which was the center of the Butua kingdom, a heterarchical society that characterized the political landscape of South-Eastern Africa during this period.

Further north of this region in what is now southern Somalia, the expansion of the Ajuran empire during the 16th century reinvigorated cultural and commercial exchanges between the coastal cities such as Mogadishu, and the mainland, in a pattern of exchanges that would integrate the region into the western Indian Ocean world.

the Valley enclosure of Great Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe

Africa and the World during the Middle Ages.

Africans continued their exploration of the old world during the Middle Ages, traveling as far as China, which had received envoys from Aksum as early as the 1st century and would receive nearly a dozen embassies from various East African states between the 7th and 14th centuries.

Another region of interest was the Arabian peninsula and the Persian Gulf, where there's extensive evidence for the presence of East African settlers from the 11th to the 19th century, when Swahili merchants, scholars, craftsmen, pilgrims, and other travelers appeared in both archeological and documentary records.

Africans also traveled to the Indian subcontinent where they often initiated patterns of exchange and migration between the two regions that were facilitated by merchants from various African societies including Aksum, Ethiopia, and the Swahili coast, creating a diaspora that included prominent rulers of some Indian kingdoms.

Foreign merchants (including Aksumites in the bottom half) giving presents to the Satavahana king Bandhuma, depicted on a sculpture from Amaravati, India

African society during the Middle Ages: Religion, Writing, Science, Economy, Architecture, and Art.

Political and cultural developments in Africa were shaped by the evolution of its religious institutions, its innovations in science and technology, its intellectual traditions, and the growth of its economies.

The religious system of Kush and the Nubian Pantheon is among the best studied from an ancient African society, being a product of a gradual evolution in religious practices of societies along the middle Nile, from the cult temples and sites of ancient Kerma to the mixed Egyptian and Nubian deities of the Napatan era to the gods of the Meroitic period.

The more common religion across the African Middle Ages was Islam, especially in West Africa where it was adopted in the 11th century, and spread by West African merchants-scholars such as the Wangara who are associated with some of the region's oldest centers of learning like Dia and Djenne, long-distance trade in gold, and the spread of unique architectural styles.

‘Traditional’ religions continued to thrive, most notably the Hausa religion of bori, which was a combination of several belief systems in the Hausalands that developed in close interaction with the religious practices of neighboring societies and eventually expanded as far as Tunisia and Burkina Faso.

Similar to this was the Yoruba religion of Ifa, which is among Africa's most widely attested traditional religions, and provides a window into the Yoruba’s 'intellectual traditions' and the learning systems of an oral African society.

Temple reliefs on the South wall of the Lion temple at Naqa in Sudan, showing King Natakamani, Queen Amanitore and Prince Arikankharor adoring the gods; Apedemak, Horus, Amun of Napata, Aqedise, and Amun of Kerma.

The intellectual networks that developed across Africa during the Middle Ages and later periods were a product of its systems of education, some of which were supported by rulers such as in the empire of Bornu, while others were established as self-sustaining communities of scholars across multiple states producing intellectuals who were attimes critical of their rulers like the Hausa scholar Umaru al-Kanawi.

The biographies of several African scholars from later periods have been reconstructed along with their most notable works. Some of the most prolific African scholars include the Sokoto philosopher Dan Tafa, and several women scholars like Nana Asmau from Sokoto and Dada Masiti from Barawa.

On the other side of the continent, the intellectual networks in the northern Horn of Africa connected many of the region’s scholarly capitals such as Zeila, Ifat, Harar, Berbera with other scholarly communities in the Hejaz, Yemen, and Egypt, where African scholarly communities such as the Jabarti diaspora appear prominently in colleges such al-Azhar. Along the east African coast, scholars composed works on poetry, theology, astronomy, and philosophy, almost all of which were written in the Swahili language rather than Arabic.

Some of Africa’s most prominent scholars had a significant influence beyond the continent. Ethiopian scholars such as Sägga Zäᵓab and Täsfa Sәyon who visited and settled in the cities of Lisbon and Rome during the 16th century engaged in intellectual exchanges, and Sägga Zäᵓab published a book titled ‘The Faith of the Ethiopians’ which criticized the dogmatic counter-reformation movement of the period. The writings of West African scholars such as the 18th-century theologian, Salih al-Fullani from Guinea, were read by scholarly communities in India.

copy of the 19th century ‘Utendi wa Herekali’, of Bwana Mwengo of Pate, Kenya, now at SOAS London.

The growth of African states and economies was sustained by innovations in science and technology, which included everything from metallurgy and glass manufacture to roadbuilding and shipbuilding, to intensive farming and water management, to construction, waste management, and textile making, to the composition of scientific manuscripts on medicine, astronomy, mathematics, and Geography.

Africa was home to what is arguably the world's oldest astronomical observatory located in the ancient city of Meroe, the capital of Kush. It contains mathematical equations inscribed in cursive Meroitic and drawings of astronomers using equipment to observe the movement of celestial bodies, which was important in timing festivals in Nubia.

While popular mysteries of Dogon astronomy relating to the Sirius binary star system were based on a misreading of Dogon cosmology, the discovery of many astronomical manuscripts in the cities of Timbuktu, Gao, and Jenne attest to West Africa's contribution to scientific astronomy.

A significant proportion of the scientific manuscripts from Africa were concerned with the field of medicine, especially in West Africa where some of the oldest extant manuscripts by African physicians from Songhai (Timbuktu), Bornu, and the Sokoto empire are attested.

18th-century astronomical manuscript from Timbuktu showing the rotation of the planets

Besides manuscripts on the sciences, religion, philosophy, and poetry, Africans also wrote about music and produced painted art. Ethiopia in particular is home to one of the world’s oldest musical notation systems and instruments that contributed to Africa’s musical heritage. Additionally, they also created an Ethiopian calendar, which is one of the world's oldest calendars, being utilized in everything from royal inscriptions to medieval chronicles to the calculation of the Easter computus.

African art was rendered in various mediums, some of the most notable include the wall paintings of medieval Nubia, as well as the frescos and manuscript illustrations of Ethiopia, ancient Kerma and the Swahili coast.

Contrary to common misconception, the history of wheeled transport and road building in Africa reflected broader trends across the rest of the world, with some societies such as ancient Kush and Dahomey adopting the wheel, while others such as Aksum and Asante built roads but chose not to use wheeled transport likely because it offered no significant advantages.

Regional and long-distance trade flourished during the African Middle Ages and later periods. In West Africa, trade was enabled by the navigability of the Niger River which enabled the use of large flat-bottomed barges with the capacity of a medium-sized ship, that could ferry goods and passengers across 90% of the river's length

Some of the best documented industries in Africa's economic history concern the manufacture and sale of textiles which appear in various designs and quantities across the entire timeline of the continent's history, and played a decisive role in the emergence of early industries on the continent.

One of the regions best known for the production of high-quality textiles was the kingdom of Kongo which was part of Central Africa's 'textile belt' and would later export significant quantities of cloth to European traders, some of which ended up in prestigious collections across the western world.

Kongo luxury cloth: cushion cover, 17th-18th century, Polo Museale del Lazio, Museo Preistorico Etnografico Luigi Pigorini Roma

The expansion of states and trade across most parts of the continent during the Middle Ages enabled the growth of large cosmopolitan cities home to vibrant crafts industries, monumental architecture, and busy markets that traded everything from textiles to land and property.

Some of the African cities whose history is well documented include the ancient capital of Aksum, the holy city of Harar, the scholarly city of Timbuktu, the ancient city of Jenne, the Hausa metropolis of Kano, the Dahomey capital of Abomey, the Swahili cities of; Kilwa, Barawa, Lamu, and Zanzibar, and lastly, the Ethiopian capital of Gondar, the city of castles.

The growth of cities, trade, and the expansion of states was enabled not just by the organization and control of people but also by the control of land, as various African states developed different forms of land tenure, including land charters and grants, as well as a vibrant land market in Nubia, Ethiopia, Sokoto, Darfur, and Asante.

The cities and hinterlands of Africa feature a diverse range of African architectural styles, some of the best-known of which include the castles of Gondar, the Nubian temples of Kerma and Meroe, the Swahili palaces and fortresses, the West African mosques and houses, as well as the stone palaces of Great Zimbabwe.

Some of the best-studied African architecture styles are found in the Hausalands, whose constructions include; large palace complexes, walled compounds, double-story structures with vaulted roofs, and intricately decorated facades.

Ruins of the Husuni Kubwa Palace, Kilwa, Tanzania

Africa during the early modern era (1500-1800)

The early modern period in African history continues many of the developments of the Middle Ages, as older states expanded and newer states appear in the documentary record both in internal sources and in external accounts. While Africa had for long initiated contact with the rest of the Old World, the arrival of Europeans along its coast began a period of mutual discovery, exchanges, and occasional conflicts.

Early invasions by the Portuguese who attacked Mali’s dependencies along the coast of Gambia in the 1450s were defeated and the Europeans were compelled to choose diplomacy, by sending embassies to the Mali capital. Over the succeeding period, African military strength managed to hold the Europeans at bay and dictate the terms of interactions, a process has been gravely misunderstood by popular writers such as Jared Diamond.

The history of African military systems and warfare explains why African armies were able to defeat and hold off external invaders like the Arabs, the Europeans, and Ottomans. This strength was attained through combining several innovations including the rapid adoption of new weapons, and the development of powerful cavalries which dominated warfare from Senegal to Ethiopia.

Contacts between African states and the Ottomans and the Portuguese also played an important role in the evolution of the military system in parts of the continent during the early modern era, including the introduction of firearms in the empire of Bornu, which also imported several European slave-soldiers to handle them.

Bornu's diplomatic overtures to Istanbul and Morroco, and its powerful army enabled it to avoid the fate of Songhai, which collapsed in 1591 following the Moroccan invasion. But the Moroccans failed to take over Songhai's vassals, thus enabling smaller states in the empire’s peripheries such as the city-state of Kano, to free themselves and dominate West Africa's political landscape during this period.

In the northern Horn of Africa, Ethiopia was briefly conquered by the neighboring empire of Adal which was supported by the Ottomans, but the Ethiopian rulers later expelled the Adal invaders partly due to Portuguese assistance, although the Portuguese were themselves later expelled.

In Central Africa the coastal kingdoms of Kongo and Ndongo combined military strength with diplomacy, managing to advance their own interests by taking advantage of European rivalries.

Dutch delegation at the court of the King of Kongo, 1641, in Olfert Dapper, Naukeurige beschrijvinge van den Afrikaensche gewesten (Amsterdam, 1668)

The Kongo kingdom was one of Africa's most powerful states during this period, but its history and its interactions with Europeans are often greatly misunderstood. The diplomatic activities of Kongo resulted in the production of a vast corpus of manuscripts, which allows us to reconstruct the kingdom's history as told by its own people.

While Kongo crushed a major Portuguese invasion in 1622 and 1670, the kingdom became fragmented but was later re-united thanks to the actions of the prophetess Beatriz Kimpa Vita, in a society where women had come to wield significant authority.

Another kingdom whose history is often misunderstood is Dahomey, which, despite its reputation as a 'black Sparta', was neither singularly important in the Atlantic world nor dependent on it.

It’s important to note that the effects of the Atlantic trade on the population of Africa, the political history of its kingdoms, and the economies of African societies were rather marginal. However, the corpus of artworks produced by some coastal societies such as the Sapi indicates a localized influence in some regions during specific periods. It is also important to note that anti-slavery laws existed in precolonial African kingdoms, including in Ethiopia, where royal edicts and philosophical writings reveal African perspectives on abolition.

To the east of Dahomey was the powerful empire of Oyo which came to control most of the Yorubalands during the 17th century and was for some time the suzerain of Dahomey. West of these was the Gold Coast region of modern Ghana, that was dominated by the kingdom of Asante, which reached its height in the 18th and 19th centuries, owing not just to its formidable military but also its diplomatic institutions.

On the eastern side of the continent, the Portuguese ascendancy on the Swahili coast heralded a shift in political alliances and rivalries, as well as a reorientation of trade and travel, before the Portuguese were expelled by 1698. In south-east Africa, the kingdom of Mutapa emerged north of Great Zimbabwe and was a major supplier of gold to the Swahili coast, and later came under Portuguese control before it too expelled them by 1695.

In south-western Africa, the ancient communities of Khoe-San speakers inflicted one of the most disastrous defeats the Portuguese suffered on the continent in 1510, but the repeated threat of Dutch expansion prompted shifts in Khoe-San societies including the creation of fairly large states, as well as towns such as the remarkable ruined settlement of Khauxanas in Namibia.

In central Africa, the rise of the Lunda empire in the late 17th century connected the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic, and the lucrative trade in copper and ivory the Lunda controlled attracted Ovimbundu and Swahili traders who undertook the first recorded journeys across the region.

Increased connectivity in Central Africa did not offer any advantages to the European colonists of the time, as the Portuguese were expelled from Mutapa by the armies of the Rozvi founder Changamire in the 1680s, who then went on to create one of the region's largest states.

ruins of Naletale, Zimbabwe

In the far west of Rozvi was the kingdom of Ndongo and Matamba whose famous queen Njinga Mbande also proved to be a formidable military leader, as her armies defeated the Portuguese during the 1640s before she went on to establish an exceptional dynasty of women sovereigns.

Africa and the World during the early modern period.

Africans continued their exploration of the Old World during the early modern period. The Iberian peninsula which had been visited by so-called ‘Moors’ from Takrur and the Ghana empire would later host travelers from the kingdom of Kongo, some of whose envoys also visited Rome.

By the 17th century, African travelers had extended their exploration to the region of western Europe, with several African envoys, scholars, and students from Ethiopia, Kongo, Allada, Fante, Asante, and the Xhosa kingdom visiting the low countries, the kingdoms of England and France and the Holy Roman empire.

Africans from the Sudanic states of Bornu, Funj, Darfur, and Massina traveled to the Ottoman capital Istanbul often as envoys and scholars. While in eastern Africa, merchants, envoys, sailors, and royals from the Swahili coast and the kingdom of Mutapa traveled to India, especially in the regions under Portuguese control, expanding on pre-existing links mentioned earlier, with some settling and attaining powerful positions as priests.

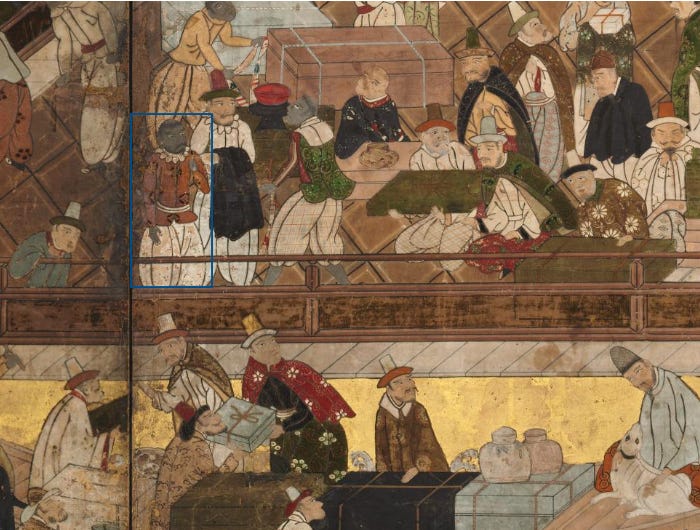

The African diaspora in India which was active in maritime trade eventually traveled to Japan where they appeared in various capacities, from the famous samurai Yasuke, to soldiers, artisans, and musicians, and are included in the 'Nanban' art of the period.

detail of a 17th-century Japanese painting, showing an African figure watching a group of Europeans, south-Asians and Africans unloading merchandise. Cleveland Museum

Internal exploration across the continent continued, especially across West Africa and North-East Africa where the regular intellectual exchanges created a level of cultural proximity between societies such as Bornu and Egypt that discredits the colonial myth of Sub-Saharan Africa.

The emergence of the desert kingdom of Wadai in modern Chad as well as the kingdoms of Darfur and Funj in modern Sudan enabled the creation of new routes from West Africa, which facilitated regular travel and migration of scholars and pilgrims, such as the Bornu saint whose founded the town of Ya'a in Ethiopia.

Africa in the late modern period (18th to 19th centuries)

Safe from the threat of external invasion, the states and societies of Africa continued to flourish.

In the Comoro Archipelago along the East African coast, the city of Mutsamudu in the kingdom of Nzwani became the busiest port-of-call in the western Indian Ocean, especially for English ships during the 17th and 18th centuries.

While the golden age of piracy didn't lead to the establishment of the mythical egalitarian paradise of Libertalia in Madagascar, the pirates played a role in the emergence of the Betsimisaraka kingdom, whose ruler's shifting alliances with the rulers of Nzwani initiated a period of naval warfare that engulfed the east African coast, before the expansion of the Merina empire across Madagascar subsumed it.

In Central Africa, the 17th and 18th centuries were the height of the kingdom of Loango which is famous for its ivory artworks. In the far east of Loango was the Kuba kingdom whose elaborate sculptural art was a product of the kingdom's political complexity, and south of Kuba was the Luba kingdom, where sculptural artworks like the Lukasa memory boards served a more utilitarian function of recording history and were exclusively used by a secret society of court historians.

In the eastern part of Central Africa, the Great Lakes region was home to several old kingdoms such as Bunyoro, Rwanda, and Nkore, in a highly competitive political landscape which in the 19th century was dominated by the kingdom of Buganda in modern Uganda, that would play an important role in the region’s contacts and exchanges with the East African coast.

In southern Africa, the old heterarchical societies such as Bokoni with its complex maze of stone terraces and roads built as early as the 16th century were gradually subsumed under more centralized polities like Kaditshwene in a pattern of political evolution that culminated in the so-called mfecane which gave rise to powerful polities such as the Swazi kingdom.

Bokoni ruins. a dense settlement near machadodorp, South Africa showing circular homes, interconnecting roads, and terracing.

In West Africa, the period between 1770 and 1840 was also a time of revolution, that led to the formation of large 'reformist' states such as the Massina Empire and the Sokoto Empire, which subsumed pre-existing kingdoms like Kano, although other states survived such as the Damagram kingdom of Zinder whose ruler equipped his army with artillery that was manufactured locally.

The 'reformist' rulers drew their legitimacy in part from reconstructing local histories such as Massina intellectual Nuh al Tahir who claimed his patron descended from the emperors of Songhai. Similarly in Sokoto, the empire’s founders and rulers such as Abdullahi Dan Fodio and Muhammad Bello debated whether they originated from a union of Byzantines and Arabs, or from West Africa. contributing to the so-called ‘foreign origin’ hypothesis that would be exaggerated by European colonialsts.

The 19th century in particular was one of the best documented periods of Africa’s economic history, especially for societies along the coast which participated in the commodities boom.

In the Merina kingdom of Madagascar, an ambitious attempt at proto-industrialization was made by the Merina rulers, which led to the establishment of factories producing everything from modern rifles to sugar and glass.

In Southern Somalia, the old cities of Mogadishu and Barawa exported large quantities of grain to southern Arabia, just as the old kingdom of Majeerteen in northern Somalia had also emerged as a major exporter of commodities to the Red Sea region and India, while the Oromo kingdom of Jimma in modern Ethiopia became a major exporter of coffee to the red sea region.

In East Africa, the emergence of Zanzibar as a major commercial entrepot greatly expanded pre-existing trade routes fueled by the boom in ivory exports, which saw the emergence of classes of wage-laborers such as the Nyamwezi carriers and exchanges of cultures such as the spread of Swahili language as far as modern D.R.Congo

Mombasa, Kenya, ca. 1890, Northwestern University

In West-Central Africa, the rubber trade of 19th century Angola, which was still controlled by the still-independent kingdoms of Kongo and the Ovimbundu, brought a lot of wealth to local African producers and traders in contrast to the neighboring regions which were coming under colonial rule.

In West Africa, participants in the commodities boom of the period included liberated slaves returning from Brazil and Sierra Leone, who established communities in Lagos, Porto-Novo and Ouidah, and influenced local architectural styles and cultures.

Africa and the World during the late modern period.

The 19th century was the height of Africa's exploration of the old world that in many ways mirrored European exploration of Africa.

African travelers produced detailed first-hand accounts of their journeys, such as the travel account of the Hausa travelers Dorugu and Abbega who visited England and Prussia (Germany) in 1856, As well as the Comorian traveler Selim Abakari who explored Russia in 1896, and Ethiopian traveler, Dabtara Fesseha Giyorgis who explored Italy in 1895.

The 19th century was also the age of imperialism, and the dramatic change in Africa's perception of Europeans can be seen in the evolution of African depictions of Europeans in their art, from the Roman captives in the art of Kush, to the Portuguese merchants in Benin art to the Belgian colonists in the art of Loango.

Ivory box with two Portuguese figures fighting beside a tethered pangolin, Benin city, 19th century, Penn museum

From Colonialism to Independence.

African states often responded to colonial threats by putting up stiff resistance, just like they had in the past.

Powerful kingdoms such as the Asante fought the British for nearly a century, the Wasulu empire of Samori fought the French for several decades, the Zulu kingdom gave the British one of their worst defeats, while the Bunyoro kingdom fought a long and bitter war with the British.

Some states such as the Lozi kingdom of Zambia chose a more conciliatory approach that saw the king traveling to London to negotiate, while others such as the Mahdist state in Sudan and the Ethiopians entered an alliance of convenience against the British. But ultimately, only Ethiopia and Liberia succeeded in retaining their autonomy.

After half a century of colonial rule that was marked by fierce resistance in many colonies and brutal independence wars in at least six countries (Angola, Algeria, Mozambique, Guinea, Zimbabwe, and Namibia), African states regained their independence and marked the start of a new period in the continent's modern history.

Conclusion

Those looking for shortcuts and generalist models to explain the history of Africa will be disappointed to find that the are no one-size-fits-all theories that can comprehensively cover the sheer diversity of African societies. The only way to critically study the history of the continent is the embrace its complexity, only then can one paint a complete picture of the General History of Africa.

Musawwarat es-sufra temple complex near Meroe, Sudan.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra on Patreon

Thank you Isaac your articles are always well received across Quora Spaces, dispelling ignorant and often racist assumptions about the African past, not only that, but it help others combatting ignorance on those spaces who tend to use ancient Egypt to combat these negative assumptions, as the only go to area of research, one of the eye opener for many is the Dar Titichitt complex , I always look forward to Mondays, again thank you.

What a dazzlingly comprehensive overview. Perhaps you have already written this elsewhere, but I would love to get a recommended reading list from you the covers all the varying and disparate parts of this story at some point