Guns, Germs and Steel in Africa: Jared Diamond and the limits of Geographic Determinism

“African prehistory is a puzzle on a grand scale, still only partly solved.”

Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel, published in 1997, is one of the most widely read works on world history and has enjoyed remarkable success at both the popular and academic levels.

In this ambitious study, Diamond seeks to explain why the modern world has been shaped by uneven outcomes that disproportionately favored Western European populations, enabling them to influence societies across the globe through conquest and colonization. He attributes this asymmetrical dominance to what he considers the most critical factors: that “some peoples developed guns, germs, steel, and other factors conferring political and economic power before others did.”

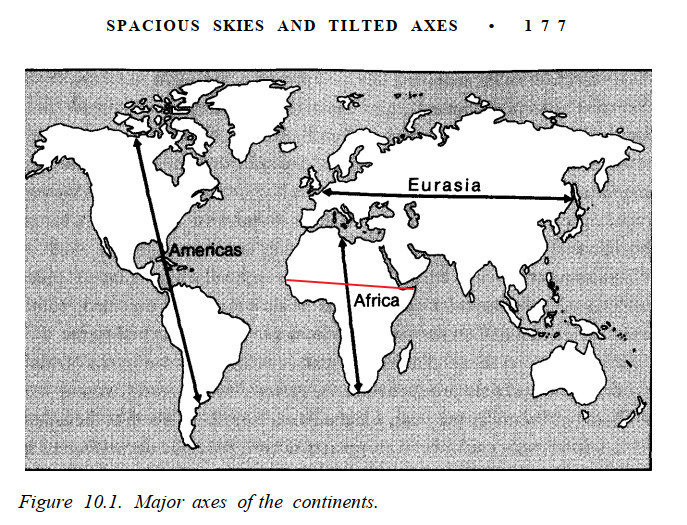

Building on this premise, Diamond claims that geographic circumstances shaped the trajectory of societies, favoring Eurasia over other regions and enabling its populations to acquire and develop the guns, germs, and steel that facilitated the colonization of the rest of the world.

According to Diamond, agriculture and animal domestication arose earlier in Eurasia, providing its populations with more time to develop technologies and immunity to diseases. He argues that this agricultural complex, along with associated technologies and pathogens, spread more rapidly along the east–west axis of Eurasia than across Africa and the Americas, which he views as predominantly oriented along the north–south axis.

In his attempt to solve the “grand puzzle” of Africa, which he sees as facing similar geographic “disadvantages” to pre-Columbian America, Diamond claims that early European colonialism in Africa was halted by tropical diseases, except in the Cape colony of South Africa, where it was stopped by the military prowess of the Bantu-speaking Xhosa.

Much of his discussion of Africa centers on the so-called Bantu “engulfing” of sub-equatorial Africa, in which he draws several problematic analogies to European colonization in Australia and the Americas.

In a separate section about the Eurasian advantage in the rapid spread of domesticates along what he considers an East-West continental orientation, Diamond includes Africa as an example of a North-South oriented continent, arguing that African domesticates spread at a much slower rate than across western Europe.

Jared Diamond’s ideas about human society and human nature continue to be enormously influential, and he is often cited as one of the first Western scholars to challenge earlier explanations that credited Europe’s colonial expansion to inherent racial superiority, instead emphasizing the role of geography and disease.

This article examines Jared Diamond’s myths and misconceptions on African history, showing that Diamond disregarded contemporary scholarship on African history, while simultaneously uncritically reproducing discredited theories of racial science that he ostensibly sought to challenge.

This article was first published on Patreon, 3 years ago.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by joining our Patreon community. Subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Who are the ‘Khoe-San’ and ‘Bantu’?

Diamond claims that the present distribution of the “pygmy” foragers of the Congo Forest region, the Hadza and Sandawe foragers of Tanzania, and the Khoisan of south-western Africa are the remnants of a once far more extensive and internally related set of populations, allegedly unified by the use of click-based languages. According to this view, these groups were “engulfed” by the Bantu-speaking farmers through conquest, expulsion, and interbreeding. (GGS pg 383-384, 385-86)

I have addressed the problems with each of these arguments in greater detail in my earlier essay on the Bantu expansion. However, it is useful to restate here the principal corrections, particularly where Diamond conflates distinct populations and historical processes that were geographically varied.

The terms ‘Khoe-San’ and ‘Bantu’ are both artificial words coined by linguists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to classify African languages. ‘Khoe’ meaning “person” is an endonym by herders in south-west Africa, while ‘San’ is an exonym used by the Khoe to refer to foragers. The two words were combined to form Khoe-San, or more commonly, Khoisan, to create a collective name for the languages spoken by the hunter-gatherer and pastoralist populations of south-western Africa.1

‘Bantu,’ by contrast, derives from a widely attested root meaning “people,” but the term as it is understood today wasn’t used as an endonym by the diverse groups that spoke the Bantu languages. Rather, it is an artificial label created by European linguists that was subsequently institutionalized and racialized through colonial administration in places like South Africa.2

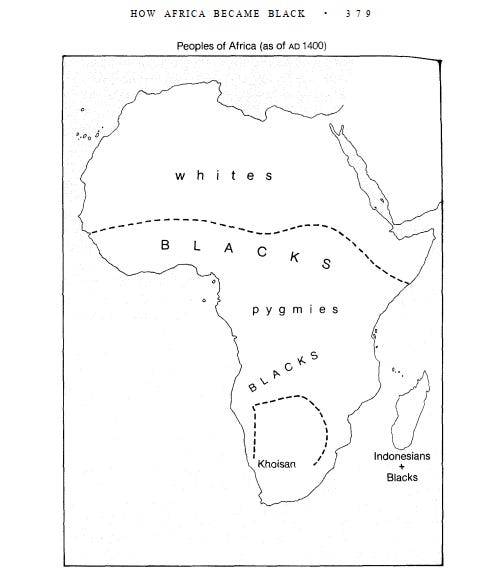

Diamond uncritically reproduces antiquated theories of colonial scientific racism in the section titled ‘How Africa became Black’, which is ironic given that he is considered to be one of the first Western academics to provide a good counter-argument against some of the more noxious forms of racist superiority and Eurocentrism. Despite acknowledging the limitations of this highly unscientific division of Africa into arbitrary races, Diamond insists that it “is still so useful for understanding history,” and it’s this reductive framework that he brings to his analysis of the Bantu expansion. (GGS pg 376-380)

Jared Diamond’s map of Africa’s “races” under the title, ‘How Africa Became Black’

The Khoe-San languages consist of five distinct and independent genealogical units: Khoe-Kwadi, Kxʼa, Tuu, and the language isolates of Hadza and Sandawe. Diamond’s image of a widely distributed prehistoric Khoe-san population that linked the click-based languages of East and Southern Africa is based on Joseph Greenberg’s (1954) now-discredited theory that the language family formed a single genealogical unit, similar to the Bantu or Cushitic languages.3

The modern Khoe-San represent populations are geographically distinct and highly differentiated, both among themselves and compared to other African populations, and have been isolated from other groups for tens of thousands of years, but they nevertheless share an ancestral cluster. This ‘ancestral cluster’ split up long before the Bantu expansion; estimated at 55-35,000 BP in the case of the splitting of the proto-Sandawe and the proto-Hadza from the rest of the proto-Khoe-San; and 20-15,000 BP for the split between the Sandawe and Hadza. Comparatively, the Bantu languages diverged from the rest of the Niger-Congo family around 5-4,000 BP.4

A recent analysis of several studies on the genetic ancestry of modern Hadza and Sandawe foragers by the geneticists Viktor Černý and Luísa Pereira revealed that both groups showed a high genetic distance from the Khoe-San. “Both the Hadza and Sandawe showed a high genetic distance from the San, being as similar to the Khoi as they are to any other Bantu group or to each other. Thus, this evidence did not support a common ancestry for the Khoisan and East African foragers sharing the click sounds… the divergence of all contemporary groups of analyzed foragers was completed long before the arrival of Bantu farmers”.5

The relative genetic homogeneity observed among most Bantu-speaking populations, together with the fact that the highest levels of admixture between the Khoe-San and Bantu speakers are concentrated among communities living in closest geographic proximity to one another, suggests that the spatial distribution of Khoe-San speaking communities during the period of the Bantu expansion may not have differed substantially from their present locations in the late 19th/early 20th century.6

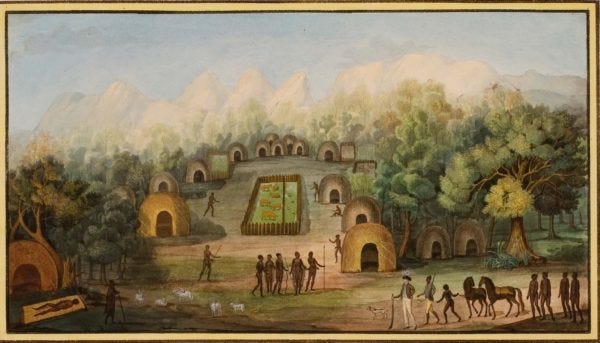

18th-century drawing of a village in the Khoe Kingdom of Gonaqua

We will return to this explanation for the Khoe-San’s spatial distribution in a later section explaining the limits of the military capabilities that Diamond attributes to early Bantu-speakers. For now, let’s continue with his claims on how the Khoe-San were supposedly decimated.

According to Diamond, the Bantu spread through the Congo Forest, clearing gardens, increasing their numbers, and engulfing pygmy foragers whom they pushed into the forest, using their iron weapons. The Khoisan foragers, he says, were rapidly eliminated like the aboriginal Australians were eliminated by white colonists, in an “engulfing” process involving conquest, expulsion, interbreeding, killing, or epidemics, leaving only those that the Bantu didn’t succeed in overrunning

He claims that after acquiring iron in East Africa, “the Bantu put together a military-industrial package that was unstoppable in the subequatorial Africa of the time… to the south lay 2,000 miles of country thinly occupied by Khoisan hunter-gatherers, lacking iron and crops. Within a few centuries, in one of the swiftest colonizing advances of recent prehistory, Bantu farmers had swept all the way to Natal.

(GGS pg 394-397)

The myth of the “Bantu military-industrial package” and technological superiority

Most Linguists have known since the 1970s that the Bantu expansion, which began by 3,000 BP, preceded the appearance of metallurgy below the equator during the last centuries before the common era, long after the Bantu had already populated much of central Africa.7 Their theories were confirmed by archaeological excavations in the 1980s and radiocarbon dating of the early Iron Age sites of the Urewe Neolithic between modern Rwanda, Burundi, and N.W Tanzania to around 600BC.8

Exavations in the KwaZulu-Natal, Mpumalanga, and Limpopo provinces of South Africa during the 1970s and 80s by the archaeologist Tim Maggs and others confirmed the presence of iron-age pottery around 400 CE.9 In 1995, material obtained by Klapwijk and Huffman from the Iron Age site of Silver Leaves in Limpopo was dated to 270 CE.10

According to the archaeologists S. Terry Childs and David Killick (1993), “The theory that the dispersal of ironworking was achieved by the spread of Bantu-speakers originated with Sir Harry Johnston in a series of papers written between 1880 and 1920. The Bantu expansion was recast in the late 1950s as a “package” of language, agriculture and metallurgy carried south by a new (Negroid) racial group who spoke Bantu languages. This remained the dominant theme in the later prehistory of Africa until the mid-1970s, when it became increasingly difficult to reconcile the linguistic and archaeological data.11

The site of Silver Springs in South Africa and the Urewe sites of Eastern Africa, which were known to most historians of Africa at the time of their discovery, were separated by around 900-1,000 years and some 1,400 miles, not by “a few centuries” and “2,000 miles” as Diamond claims. This suggests that the Bantu expansion was less “rapid and dramatic” than he claims. While Diamond later tempers this argument, warning against oversimplification, he nonetheless concludes: “the eventual result was still the same”. (GGS, pg 396)

While Diamond suggests a more-or-less continuous migration of Bantu-speakers southward, more recent studies suggest that the dispersal of Bantu-speaking communities in the Congo rainforest was checked by a widespread population collapse of their early Farming communities in the 4th century, and the early Bantu languages went extinct. Present-day Bantu languages in the region may descend from those (re)introduced during the later waves of expansion.12

Genetic studies of modern Bantu-speaking populations indicate that their Y-chromosome variation did not shrink with distance from the putative homeland, thus indicating that the original founder event was erased by later waves of forward and backward migrations. According to Koen Bostoen, such recurring migration/dispersion events would have led to internal language shift and language death. He suggests that present-day Bantu languages may not reflect the distribution of their ancient precursors.13

Although Diamond occasionally acknowledges the complexity of the Bantu expansion, his comparisons to ‘Aboriginal Australia’ and ‘Indian California’; which were contexts of extreme settler violence, implicitly echo apartheid-era claims that Bantu-speaking communities were recent arrivals, thereby legitimizing their dispossession.

Homesteads with road junctions and terraces at Rietvlei in the Bokoni ruins, South Africa

Evolution of the relations between the Khoe-San, European, and Bantu-speaking population in southern Africa’s military history.

While we know little about what exactly happened when the small bands of Bantu-speakers encountered the Khoe-San, the historical evidence from southern Africa suggests that it was unlike the analogy that Diamond portrays of white Australian colonists decimating aboriginal groups.

The military history of southern Africa, which is relatively well documented from the 15th century, suggests that the disparity in military strength between Khoe-San speakers, Bantu-speaking communities, and European settlers emerged only relatively recently, following the consolidation of more centralized states in the late 18th century and the concurrent expansion of the Cape Colony.

To illustrate just how little of an advantage the Bantu-speaking societies had over the Khoe-San speakers, we can use an example of the early military engagements between the well-armed Portuguese sailors and Dutch settlers whose incursions were initially repulsed by the Khoe-San. (A more complete outline is provided in my essay on the social history of the KhoiKhoi)

Upon reaching southern Africa in 1487, Europeans encountered pastoralist populations along the western coast of South Africa, who are presumed to be Khoe-speakers, since they were herders.

The earliest account of the encounter between the Khoe and the Europeans took place in November 1497, when Vasco Da Gama landed on St Helena Bay and later at Mossel Bay. The initially peaceful encounter turned violent after the Portuguese used the Khoe’s watering holes without permission. A small skirmish ensued with the Khoe throwing assegais (spears) while the Portuguese fired their crossbow and killed one. Vasco Da Gama’s crew erected a stone cross, which was pulled down by the Khoe before the former left.14

The next Portuguese ship to land on the South African coast came in 1503 and was led by Antoni de Saldanha, whose crewmen clashed with the Khoe after a failed attempt to trade mirrors and glass beads for two sheep and a cow. The Khoe ambushed de Saldanha’s party, wounding him and taking back the animals.

De Saldanha was later followed by Francisco de Almeida, the viceroy of Portuguese India (whose ships bombarded kilwa). De Almeida landed on Table Bay in March 1510 and his crew seized one of the Khoe as a hostage to force the latter’s peers to bring more cattle. This backfired when the Khoe, “outraged at this violation of their hospitality”, immediately attacked the Portuguese. The next day, de Almeida marched on the Khoe settlement with a force of 150 and forcefully seized the animals and children, forcing the Khoe to retaliate by mustering a force of 170 and annihilating the Portuguese force, killing 50 of them at the Battle of Salt River.

As one chronicler describes the battle:

“the blacks began to come down from where they had assembled in their first fright, like men who go to risk death to save their sons, And although some of our folk began to let the children go, the blacks came on so furiously that they, came into the body of our men, taking back the oxen; and by whistling to these and making other signs, they made them surround our men, like a defensive wall, from behind which came so many fire- hardened sticks that some of us began to fall wounded or trodden by the cattle.”15

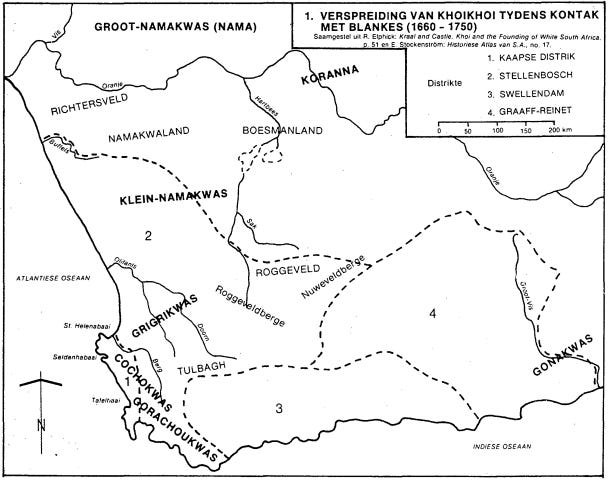

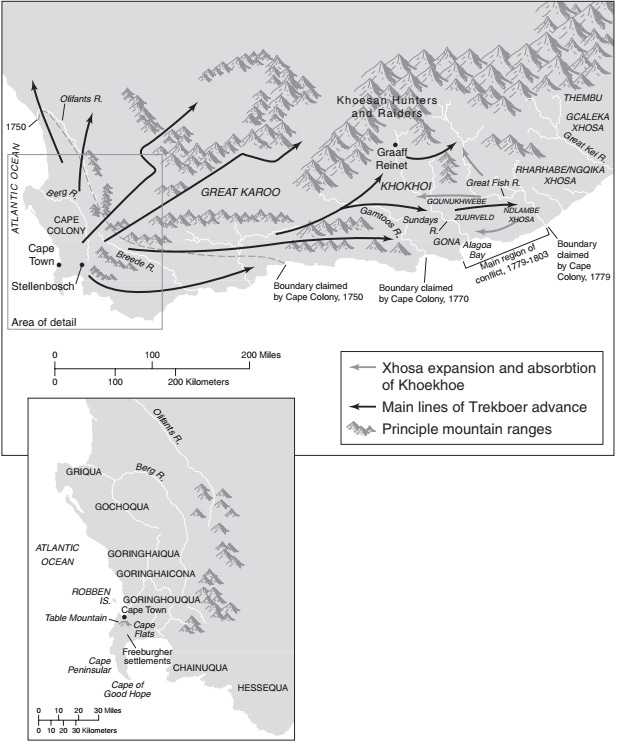

Map of southwestern Africa showing the location of the various Khoe-San groups in the 16th and 17th centuries.

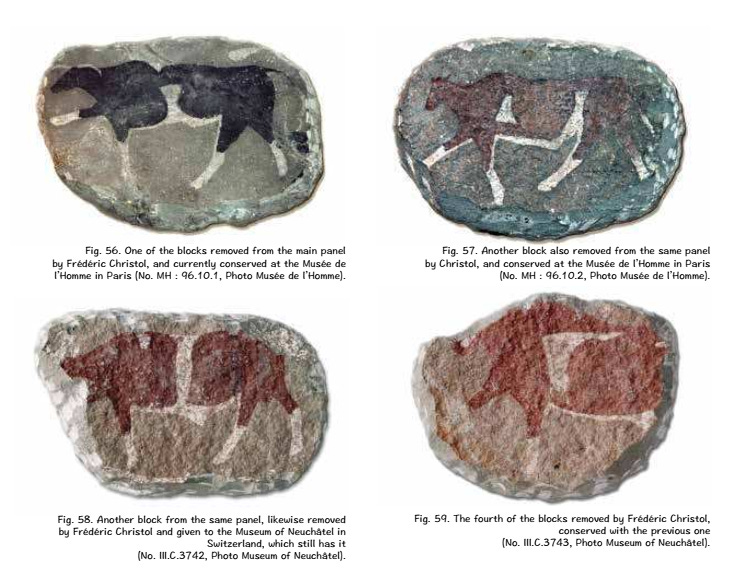

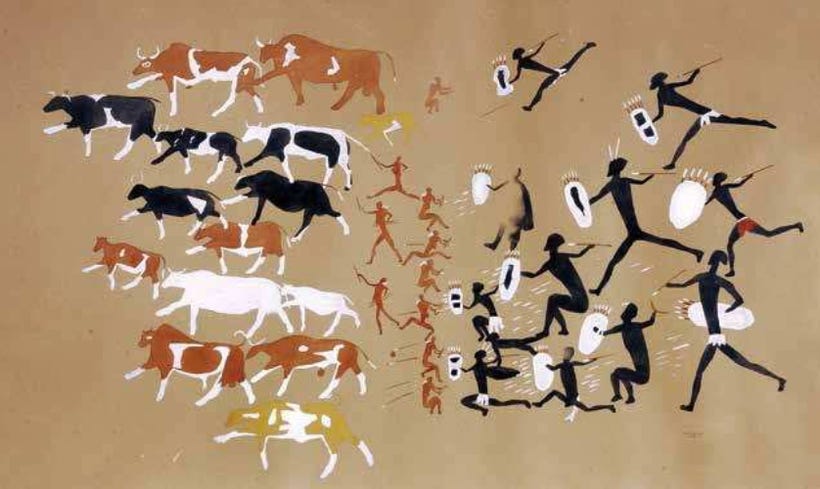

Undated cave painting from Cristol cave, south Africa, showing the types of cattle herded by the region’s pastoralists.

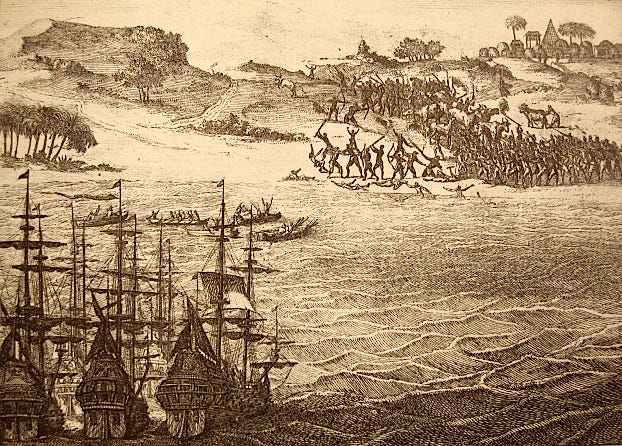

Death of Francisco d’Almeida at the Cape of Good Hope, 1510. engraving by Pieter van der Aa, ca 1700

80 years would pass before another European ship dared to land on Khoe territory.

Contacts between the Khoe-San and European trading ships resumed in the 1590s and continued through the early founding of the Dutch Cape colony after 1652. While these early contacts were initially peaceful, they soon devolved into conflict as the European settler population grew, farms expanded, and the demand for supplies of livestock outstripped the Khoe-San’s ability to meet them.

The Dutch bypassed neighboring Khoe communities (such as the Cochoqua) to send scouting parties further inland, inevitably leading to a series of wars between the Khoe and the Dutch in 1659 and 1673-1676. While the Dutch forces were about as large as the Portuguese forces of de Almeida about a century and a half prior, they had additional and vital support from local allies; the Chainouquas, another Khoi-speaking group that was a rival of the Cochoqua.16

In the succeeding decades, the Dutch colony expanded as it acquired permanent control of the land at the expense of the Khoe-San, whose grazing, hunting, and settling rights were reduced. The alliances the Dutch settlers had made with ‘friendly’ Khoe-San groups became asymmetrical, while the more ‘hostile’ groups became the target of slave raids by the treckboers. The colonial society became increasingly stratified and racially segregated, with the Khoe-San being reduced to indentured servitude.17

The colony that had initially been confined to a small territory of less than 50km for half a century grew rapidly over the 18th century, occupying nearly 10 times as much land, until it reached the borderlands of the Xhosa polities along the Fish River, where the expansion stalled.

The Early Cape Colony Showing African and Boer Settlements. Map by Aran S. MacKinnon, Adapted from K. Shillington.

While Diamond correctly observes that it was the Xhosa’s military prowess that halted the Dutch advance (GGS pg 397), He overlooks the Khoe-San’s initial success in repelling Portuguese and Dutch and oversimplifies the alliances which eventually gave Dutch settlers an advantage over the Khoe-San. He also exaggerates the speed of the colony’s expansion to the Fish River, which took place after 1778-9, not 1702; thus overstating the differences between the Khoe-San and the Xhosa’s military capacity, and assumes that the Xhosa had always possessed a military advantage over the Khoe-San.

Jared Diamond’s image of “steel-equipped Bantu farmers” is more representative of the large, centralized, militant states of the 19th century, such as the Zulu and Ndebele kingdoms, but not of the relatively small, segmented states that were found in the region during the 16th century, nor even of the Xhosa in the 19th century.

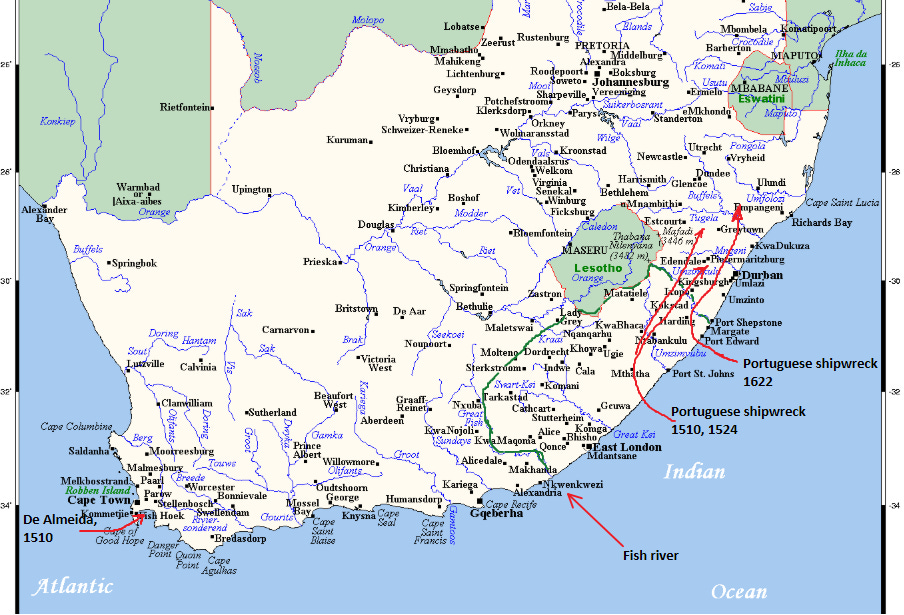

Approximate locations of the places visited by the shipwrecked Portuguese crewmen (in red), and the extent of the Xhosa polities (in green).

According to Portuguese accounts of shipwrecked crewmen from 1552 and 1554, the Bantu-speaking communities they encountered near the Mthatha and Mzimvubu rivers (Eastern Cape province, about 150km north of the Fish river), did not possess better weapons than the Khoe, being only armed with “assegais with iron points” and “many wooden pikes with their points hardens in the fire.”18

Most of the region between the Eastern Cape and the southern KwaZulu-Natal province was just as sparsely populated as the Western Cape, and the Portuguese spent weeks before encountering a sizeable settlement or a ruler with a large following, but the population steadily increased as they travelled northwards.

Along the way, the hungry and desperate crewmen traded with some of the local communities for cattle, and reportedly seized one of the Africans, “cut him up and roasted him” to eat him, which forced the Africans to assemble a fighting force to drive off the Portuguese. In the fierce fighting that followed, the Africans threw “so many assegais that the air was darkened by a cloud of them” but the Portuguese fought hard and ultimately won a costly victory, but were ultimately driven off.19

While these presumably Bantu-speaking communities of Natal had managed to drive off the Portuguese, they did not defeat them in actual combat as the Khoe-San had, and there is no indication that they had better fighting formations than the Khoe-San, who utilized their cattle, numbers, and organization to surround and defeat the forces of a famous Portuguese conquistador.

While these two battles that occurred in 1510 and 1524 on either side of the country may not tell us a lot about the political and military organization of the Khoe-San and Bantu-speaking groups, they provide important clues regarding the relative strength of their societies in the early 16th century, nearly 1,300 years after the first Bantu-speaking communities arrived in the region.

Archeological evidence from South Africa indicates that while material culture associated with Bantu-speaking communities is present in the region by 270 CE, the formation of more complex societies began much later, at sites such as Shroda (890-970 CE), K2 (1000-1220), and Mapungubwe (1220-1300).

Excavations of the stone-ruined sites of the HighVeld and the Bokoni ruins , which were settled from the 14th to 19th century, suggest that these early settlements were relatively egalitarian/heterarchical, without a sharp overarching hierarchy dividing elites and commoners.20

Settlement wards were organized based on lineages under local rulers who were mostly autonomous.21 In some of these settlements, iron was relatively scarce and was mostly obtained through trade with neighbouring polities,22 contrary to the historic stereotype of later Bantu-speaking communities as a warlike people armed with iron weapons.

By the late 18th century, some of the rulers accumulated wealth and centralized their political power over neighboring groups, resulting in the growth of large aggregated capitals like Molokwane, Marothodi, and Kaditshwene, whose population rivalled the Dutch colonial capital of Cape Town.

Map of South Africa showing some of the largest stone ruins in the HighVeld

Molokwane ruins.

Kweneng ruins.

It was during this period that documentary accounts first describe the presence of large armies, more centralized polities ruled by Kings with subordinate chiefs, and the sort of military prowess associated with the 19th-century Bantu-speaking kingdoms.

One account, written in 1798-9, describes the Tembe kingdom between Maputo Bay and Kwazulu-Natal, whose ruler, “King Capelleh” (Muhadane) had several subordinate chiefs below him, and controlled a relatively large territory (about 200x100 miles , 50,000 sqkm). He had “a guard of thirty men, armed with spears and battle-axes made out of large spike nails. Some of them had shields made out of rhinoceros hide.” This king restricted access to his chiefs, monopolized external trade, and appointed officers in charge of organizing the local sailboats that supplied passing ships with provisions.23

Between the late 18th to early 19th century, larger, more powerful states emerged, as their armies gradually incorporated the use of new technologies, such as horses in Lesotho and firearms among the Zulu, into the pre-existing arsenal of traditional weapons.

Yet despite the gradual centralization and militarization of the late 18th to early 19th century, the early Dutch-Xhosa wars of the 1779-81, 1793, 1799-1803, involved only a few hundred combatants on both sides, suggesting no significant changes in mobilization since the 16th century.

It was only after the British conquered the Cape colony in 1806 and began sending larger colonial armies to the frontier that the Xhosa began mustering larger armies, eg, in 1819, when an army of 6-10,000 Xhosa besieged Grahamstown. Similar numbers for the Ndebele and Zulu kingdoms are documented after the 1820s, especially during the Great Trek (1836-40).24

Map showing the kingdoms of Southern Africa in the early 19th century

As with most states in African history, it’s important to note that these large kingdoms were not homogenous polities made up of one ethnic group, but were instead comprised of multiple social groups, lineages, and clans that recognized the authority of one ruler or founder.

Many of the modern “tribes” and “languages” are in fact named after some of these pre-colonial states, even though the peoples and languages are themselves much older, and extended beyond the territorial reach of the pre-colonial states.

In the case of the Xhosa and their semi-legendary founder-king Tshawe, the historian Jeff Peires (1982) writes: “the limits of Xhosadom were not ethnic or geographic, but political: all persons or groups who accepted the rule of the Tshawe thereby became Xhosa.” The kingdom’s clans claimed both Bantu and Khoe-San origins. Khoi-San speaking groups such as the Gona, Dama, and Hoengiqua “were not expelled from their ancient homes or relegated to a condition of hereditary servitude on the basis of their skin colour. They became Xhosa with the full rights of any other Xhosa.”25

Traditional histories and Portuguese accounts indicate that the founding of the kingdom by Tshawe is set some time before 1675. An earlier Portuguese account from 1622 which describes small chiefdoms around Trans-Kei (Eastern Cape), indicates that intermarriages between the Khoe-San and AmaXhosa communities predated the emergence of the kingdom:

“These Negroes are whiter than mulattoes; they are stoutly built men… we could never understand a word these people said, for their speech is not like that of mankind, and when they want to say anything they make clicks with the mouth”26

It wasn’t until the 18th century that the Xhosa polity of Tshawe, itself made up of admixed social groups, expanded into neighbouring Khoe-San (and Bantu) speaking regions, forming alliances with some while subjugating others. The kingdom encountered by the Dutch in 1779, was a formidable state, albeit one that was relatively young and not centralized, with each chief and their council retaining significant autonomy, especially over matters of war, forming alliances, as well as grazing lands and farmlands.27

The historical evidence outlined above indicates the Xhosa polities lacked decisive military advantages over Khoe-San communities and were insufficiently centralized to sustain rigid social hierarchies comparable to those of the Cape colony. It is therefore implausible that their ancestors two millennia earlier possessed the capacity to carry out large-scale displacement or mass violence of the kind associated with the colonization of the Americas and Australia.

Evidence from elsewhere in the region indicates that even in less symbiotic relationships between farmers and foragers, sustained dominance by the former emerged only relatively recently, primarily during the colonial and postcolonial periods.

In the case of the Hadza of northern Tanzania, much of their core territory remained exclusively occupied by foragers until the mid-20th century, with significant farmer encroachment occurring only from the 1950s, near the end of the colonial period. Hadza social life was profoundly disrupted only later, through forced resettlement policies in the postcolonial era of the 1960s and 1970s.

Earlier interactions were limited: their first documented violent encounters date to the late 19th century, primarily with Maasai pastoralists, while a brief and potentially exploitative relationship with Isanzu farmers emerged during the short-lived ivory boom of the same period before quickly subsiding. Overall, the evidence suggests that the Hadza have occupied largely the same territory since the arrival of Bantu-speaking populations in the region, with sustained and unequal relations with farmers and herders developing only in recent history.28

In the case of the Aka foragers of the southwestern Central African Republic, the establishment of European settler farms in 1910 and the colonial economy’s exploitation of forest products such as ivory, rubber, copper pushed the farmers into the forager regions (to escape colonial taxes and labor), and the Aka adopted farming from their new neighbors. By the postcolonial period, the Aka foragers were now moving into farmer settlements to exchange their labor and forest products for money. This represented a significant interaction tied to the modern economy, which in all likelihood, didn’t predate the 20th century.29

In the mid-late 19th century, the growth of the lucrative ivory trade and the increasing penetration of the European colonists in south-western Africa reduced forager communities of the Basarwa and the !kung from equal partners in a symbiotic relationship with the Bantu-speaking Tswana to a marginalized class. While the Basarwa had long adopted cattle herding and could raid the cattle of the Tswana and other groups, this balance of power changed dramatically at the end of the 19th century.30

In summary, even when contemporary farmer–forager relationships are taken as a point of comparison, it is unlikely that incoming Bantu-speaking communities in the pre-modern period, especially during the early phases of their dispersal, possessed significant socio-political advantages over foragers solely by virtue of their access to iron weaponry.

Enigmatic cave painting of a battle scene, in the Christol cave, first documented and reproduced in the 19th century. While often assumed to show a singular battle between San raiders and Bantu, Interpretations of such images evade simple explanations, as such paintings were not made by one individual at one point in time but by several people over many years. They also utilize visual motifs and color symbolism whose meaning is lost to most scholars, who instead project their own understandings of motifs and color symbolism onto the paintings.31

African military strength, not tropical diseases, determined the success or failure of European Colonization.

Diamond moves on from the Bantu-expansion, “to turn to the remaining question in our puzzle of African prehistory: why Europeans were the ones to colonize sub-Saharan Africa.”

He claims that “Europeans entering Africa enjoyed the triple advantage of guns and other technology, widespread literacy, and the political organization necessary to sustain expensive programs of exploration and conquest” but that for Africans, the spread of all three technologies was slowed by Africa’s geographic orientation, with its major axis is north-south, whereas Eurasia’s is east-west, thus giving Europeans a significant advantage to enable their colonization of Africa. (GGG pg 398-399)

He suggests that this advantage immediately manifested itself when Vasco DaGama’s fleet bombarded the (Bantu-speaking) Swahili city of Kilwa in 1498** and compelled its ruler to surrender. He presents this example in a manner analogous to what he claimed the Khoe-san foragers were faced with when they first encountered the Bantu Farmers 2,000 years ago, or with the Dutch settlers in 1652.

(**This actually occurred in 1505. Vasco Da Gama only threatened Kilwa, but bombarded Mogadishu, Lamu, and Zanzibar.)

Diamond skips over the inconvenient truths of why Kilwa (ie; Tanzania) did not become a permanent Portuguese colony, unlike the Cape colony. He instead advances an unsatisfactory third explanation for the delayed onset of European colonization: disease. Elsewhere in the book, Diamond asserts that tropical diseases “explain why the European colonial partitioning of New Guinea and most of Africa was not accomplished until nearly 400 years after European partitioning of the New World began.” (GGS pg 214)

All of his assertions, that “superior” technology gave Europeans a decisive advantage in places where colonies were established in Africa, that early colonialism failed because of the disease barrier, and that Africa is mostly oriented north-south so its domesticates diffused slowly, are false, as I will cover below.

European Colonial Engagements in West, East, and Central Africa before the 19th Century and the Limits of the Disease Barrier

Contrary to Diamond’s claims, the Dutch Cape Colony in what is today South Africa was neither the only important European colonial possession in pre-19th-century Africa, nor was it the oldest.

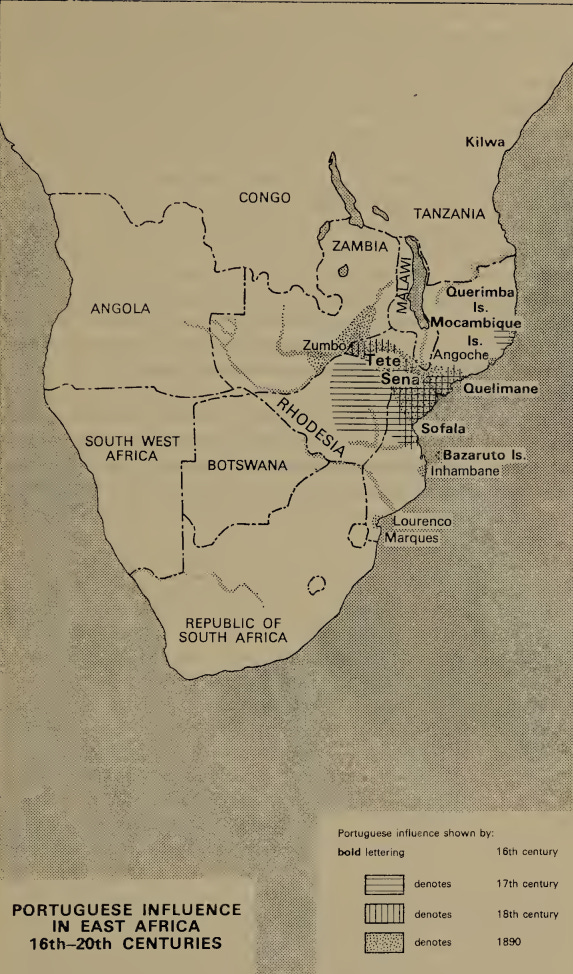

From the 15th and 17th centuries, the most ambitious colonial expansion in Africa before the Berlin conference of 1884 was undertaken by the Portuguese. These invasions were concentrated in regions characterized by high burdens of tropical disease and areas supposedly disadvantaged by Africa’s north–south axis

A time-travelling Jared Diamond in the 16th century would be forgiven for thinking that large parts of Africa would soon become a Portuguese colony like Brazil. Instead, the “superior technologies” of the Portuguese offered them few advantages and resulted in the largest loss of European lives on the African battlefield before the Italians at Adwa.

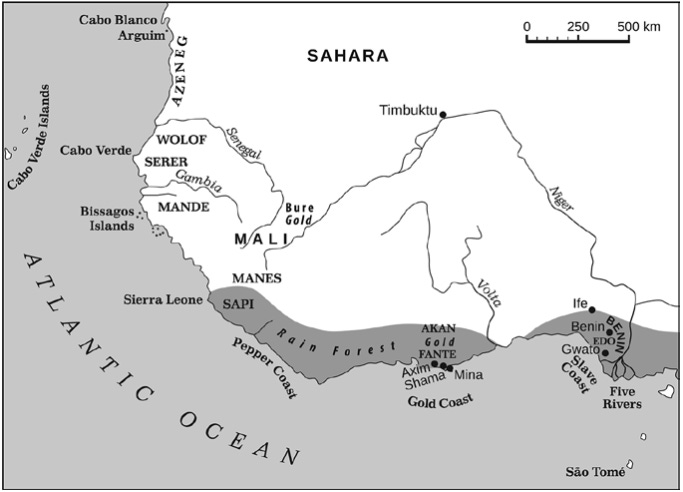

West African coast during the early Portuguese expansion in the 15th century

While early Portuguese sailors during the 1430s-50s had been accustomed to raiding the thinly populated settlements of the Azeneg (Berbers) along Mauritania’s coast, their engagements with the more organized ‘black’ armies south of the Senegal river (Wolof and Serer), who were armed with poisoned arrows and spears, quickly put an end to this.32

The Africans were undeterred by the “superior” weaponry of the Portuguese, such as cannons and crossbows. When the battle subsided, and the Portuguese approached the Africans diplomatically, asking them why they attacked the caravels, to which the Africans replied “that they firmly believed that we Christians [Europeans] ate human flesh, and that we only bought negroes to eat them: that for their part they did not want our friendship on any terms, but sought to slaughter us all, and to make a gift of our possessions to their lord.”33

After these early military defeats, diplomacy became the default relationship of all future Portuguese missions in West Africa. European coastal forts in the Upper Guinea, the Gold Coast, and the Bight of Benin were established only after obtaining permission from neighboring African polities. These forts were often at the mercy of the African states, being dependent on them for provisions and trade, and were at times the target of attacks from the armies of the inland kingdoms; most famously Dahomey in 1727 and Asante from 1807-1824.34

Later European interlopers who hadn’t learned the same lessons paid a heavy price when they attempted to invade the region. In the Casamance-Gambia region of southern Senegal, an account from 1615 mentions that the Falupos and Arriatas (sections of the modern Diola/Dyula/Juula groups) were reportedly in the habit of plundering European ships and enslaving their crew:

They are described as “mortal enemies of all kinds of white men. If our ships touch their shores they plunder the goods and make the white crew their prisoners, and they sell them in those places where they normally trade for cows, goats, dogs, iron-bars and various cloths. The only thing these braves will have nothing to do with, is wine from Portugal, which they believe is the blood of their own people and hence will not drink”35

On the eastern coast of Africa, despite bombarding Swahili cities in present-day Kenya and Tanzania and briefly occupying some in the early 16th century, the Portuguese were unable to establish lasting colonial control. It was only by forging local alliances and exploiting existing rivalries that they were able to consolidate their authority along the coast by the 17th century.

Map of the Swahili coast showing the city-states

The length of the Portuguese occupation of each city varied greatly. The ruler of the city of Kilwa, the city mentioned in Jared Diamond’s account, recognized Portuguese suzerainty for just seven years after its bombardment in 1505.

It is worth noting that Kilwa possessed access to similar “superior technologies,” including writing and navigation. Yet these conferred no advantage against the Portuguese forces of Francisco de Almeida. In contrast, the same Portuguese army was decisively defeated by Khoesan spearmen in 1510, who killed de Almeida and routed his troops despite lacking such technologies.

When the Portuguese re-conquered the city in the 1610s, it was part of a wider colonization of the coast that began at Mombasa in 1593, and was only enabled by the use of local allies, especially Malindi, whose ruler was granted 1/3 of the customs revenue from Fort Jesus.

Unlike the West African forts, which did not become the bases for long-term domination, Fort Jesus was the capital of a vast Portuguese coastal colony extending from Malindi in Kenya to Sofala in Mozambique. Portuguese soldiers, traders, priests, and other settlers were established permanently on Mozambique island, Zanzibar, Faza, Siyu, Sofala, and Mombasa for nearly a century until their expulsion in 1698 when Fort Jesus was surrendered to a Swahili-Omani fleet.

This extensive colony thrived in some of Africa’s most malaria-prone regions. Although the Swahili possessed writing and naval technology; advantages not shared by coastal West Africans or southern Africans, these conferred little practical benefit against Portuguese forces. Similarly, malaria did not deter Portuguese settlers, who maintained a 105-year occupation of Mombasa, exceeding the duration of British colonial rule from 1895 to 1963. Ultimately, it was local political dynamics, rather than technology or disease, that determined the successes and failures of resistance to Portuguese control.

Mombasa, Kenya, ca. 1890

After failing to establish a foothold in West Africa, the Portuguese redirected their efforts toward sub-equatorial Africa, expanding into west-central Africa in the 1550s and southeastern Africa in the 1600s, with the ambitious aim of linking their African holdings across the continent. Unlike earlier campaigns in West and southern Africa, these incursions relied heavily on local allies, whose auxiliary forces often outnumbered the Europeans by as much as thirty to one.36

These alliances were fluid and complex, shifting according to converging interests and the relative strength of rival states, and at times African kingdoms skillfully exploited competition between European powers such as the Dutch and the Portuguese.

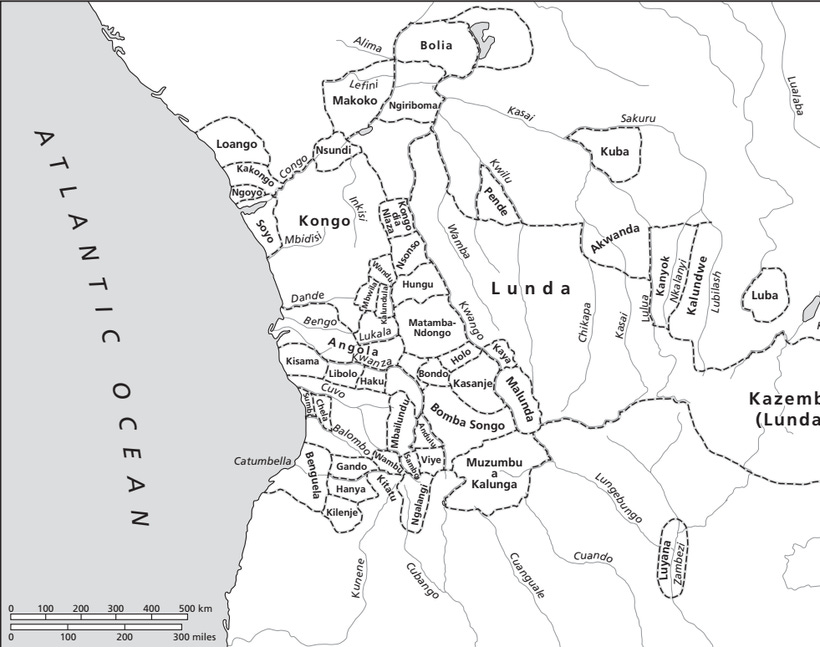

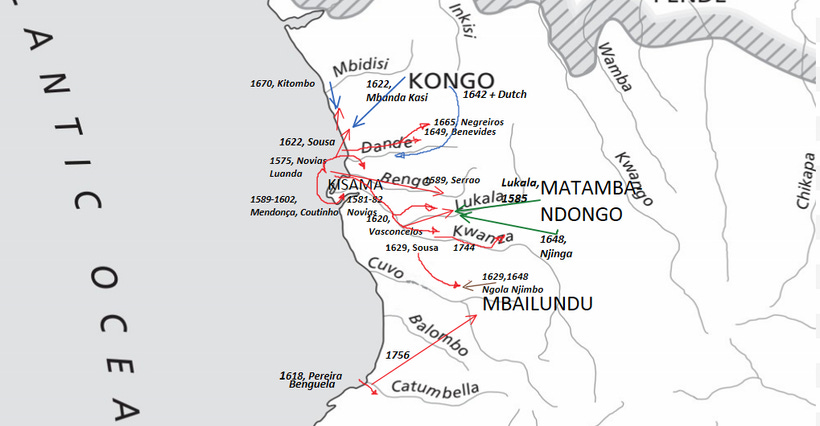

Here’s a quick summary of Portuguese invasions and defeats in west-central Africa, taken from John Thornton’s A History of West-Central Africa (pages shown in brackets).

Map of Portuguese invasions of west-central Africa (in red) and counter-attacks by Kongo (blue) and Ndongo (green). beginning with the year, name of Portuguese commander (or, in the African case, important figure/battle), and colonial possession (in this case, only Luanda and Benguela, see map above)

In west-central Africa, the Portuguese coastal colony of Angola was founded in 1571 with the assistance of Kongo’s forces to conquer their southern neighbor, Ndongo, in return for Portugal assisting Kongo fend off an invasion from an interior group. But this Portuguese army of 600 musketeers didn’t land on Luanda until 1575, and was initially reduced to a mercenary unit used by both Kongo and Ndongo to fight their own internal wars. (pg 78, 84)

In March 1580, a combined Kongo-Portugal army (which was really serving Kongo more than Portugal) was defeated by Ndongo, despite having several hundred Portuguese musketeers. (pg 85)

In 1581-1582, the Portuguese force led by Dias de Novais managed to secure local alliances of petty rulers (sobas) in the region south of Kongo, against Ndongo. He also built small colonial forts along the Kwanza. (pg 86)

In 1585-1586, Ndongo, which felt threatened by the new Portuguese alliances, decided to attack the Portuguese in the latter’s stronghold but was defeated. By this time, Ndongo had adopted the use of firearms. (pg 88)

In December 1589, Dias’ successor Luis Serrão builds an army of 15,000 with 128 Portuguese musketeers to attack Ndongo in the latter’s stronghold but is crushingly defeated at the Lukala River by a Ndongo-Matamba force, forcing him back to allied territory. (pg 91-93)

In 1594, the Portuguese under Francisco de Almeida (unrelated to the one who was killed in 1510) sent a force of 130 musketeers and cavalry to raid the Kisama region for slaves and seize its salt mines, but was defeated by the dispersed forces of the region armed with spears (pg 101)

In 1596-1598, the Portuguese under Furtado de Mendonça abandoned interior conquests and focused on the vicinity of Luanda along the Bengo river, where they scored some minor victories (pg 102)

In 1601-1602, the Portuguese under Rodrigues Coutinho finally managed to score a victory in Kisama after a series of minor defeats from local forces, and they secured a few alliances along the way (pg 107)

In 1618, the Portuguese under Cerveira Pereira managed to establish a small colony at Benguela by defeating a local soba and thus winning the alliance of other sobas. Their colony is, however, much smaller than Angola and even more reliant on the local allied sobas. (pg 115,158, 197)

In 1619-1620, while Ndongo was faced with an imbangala threat from the interior, the Portuguese under Mendes de Vasconcelos allied with the imbangala to score a major victory against Ndongo’s army and allowing them to expand their Angola colony. (pg 117-119)

In December 1622, the Portuguese under Correia de Sousa decided to attack Kongo, with a massive force of 30,000, including several hundred musketeers, he began with the province of Mbamba whose duke he defeated, and advanced to Mbanda Kasi, where his forces were crushingly defeated by Kongo’s army of 20,000. Correia was forced into exile by the Angolan settlers and died in a Lisbon prison. The wrongfully enslaved baKongo were returned to Kongo from Brazil following the demand of Kongo’s rulers. (pg 129-136)

1626-1629, the Portuguese under Fernão de Sousa resumed operations in Ndongo using imbangala allies and the puppet Ndongo king, he pursued Queen Njinga, who also claimed the throne. (pg 151,155)

September 1642, a combined Dutch-Kongo force scored several victories against the Portuguese incursions in the Dembos region and along the Bengo river. (pg 165)

1644-1648, Queen Njinga of Matamba and Ndongo, fighting with equally matched forces that included Dutch musketeers, defeats several Portuguese incursions, managing to advance into the Angolan colony, but she also suffers some losses. (pg 169-171)

1648, Portuguese incursions east of Kasanje are met with defeat near the source of the Keve river by Ngola Njimbo, as he had done to a similar incursion in 1629. (pg 191)

1649, while the Portuguese under Salvador Correia de Sá e Benevides sent an army with 300 musketeers to attack and raid Mbwila (a semi-autonomous vassal of Kongo near the mouth of the Dande river), but failed to score a victory (pg 172)

1665, Kongo and Portuguese Angola under Vidal de Negreiros, support rival claimants of Mbwila’s throne, both sent equally matched armies against each other in a lengthy engagement that ended in Kongo’s defeat (pg 182)

—Kongo enters a period of civil war, and its province of Soyo emerges as kingmaker

October 1670, Portuguese forces seeking to crush Soyo’s power, advanced with an army of 500 musketeers and several thousand allied imbangala, but were crushed at Kitombo, and the entire force was annihilated (pg 185)

—The Portuguese wouldn’t deploy large armies in Kongo until 1855 and 1914.

In 1744, the Portuguese attacked Matamba with a massive army of 26,000, but only managed to sack Queen Ana II’s capital, the latter of whom had already retreated I anticipation, denying the overextended army a victory (pg 240)

— The 1744 campaign would be the last major Portuguese invasion into Matamba until 1909.

In 1747, the Portuguese under João Jacques de Magalhães attacked the Kisama region near the coast after failing in several campaigns during 1688, 1695, 1710, and 1735 to establish Portuguese authority in the region. (pg 250)

In 1756, A Portuguese force combining resources from Angola and Benguela, managed to capture the King of Mbailundu and attempted to install a loyal King but he was overthrown, and the Kingdom only maintained nominal vassalage to Portugal, the latter’s having no authority outside protecting its traders (pg 299)

Having failed to conquer the kingdoms of the interior, the Portuguese concentrated on their coastal colony of Angola by instituting several reforms that were ultimately failures. The first was to displace Kongo’s cloth currency with copper coins; this was abandoned after a year. The second was Lusitanizing the administration with qualified Portuguese rather than “mulattos” and Africans; this too failed. The last reform was establishing a steel and iron foundry in Angola, but this too failed (pg 290-291)

The colony of Angola was the oldest and largest permanently occupied European settlement in Africa from 1575 to 1700, when its white population was surpassed by the Cape Colony.37

The Portuguese would only resume large-scale colonial wars in the west-central African interior in the late 19th century, ending with the occupation of Kongo’s capital in 1914.

This outline reveals that despite their intention of establishing a large colony in west-central Africa, the Portuguese armies, with their superior technologies, were nevertheless routinely defeated in their wars with African armie,s whether the latter were armed with guns or with spears.

As summarized by John Thornton, “Clearly there was no automatic or overwhelming technical or organizational superiority, although Military systems of both countries were affected by the contact. It was not until the age of the Maxim gun, in fact, that Africans could be overwhelmed, in Angola or anywhere, by sheer military superiority.”38

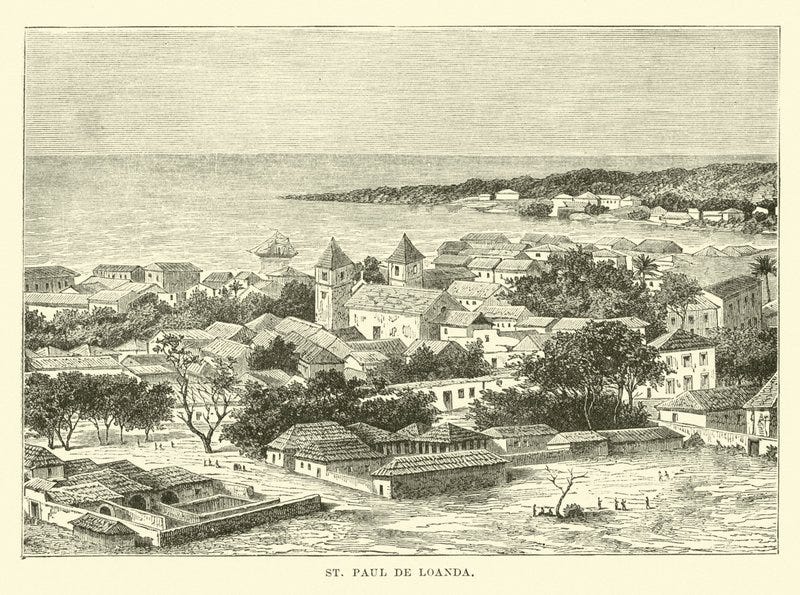

Luanda in the early 19th century

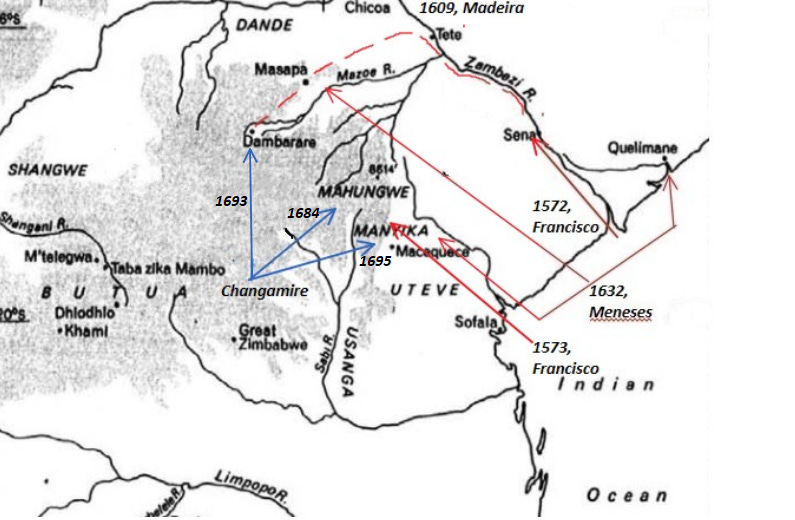

Chronology of Portuguese colonial invasions and defeats in South-east Africa.

A similar attempt at establishing a colony in the interior of southeast Africa by conquering the Mutapa kingdom also failed, as I explored in my essay on the kingdom of Mutapa and the conquistadors.

This was despite the Portuguese’ superiority in military technology, with an army five times larger than the one Pizarro used to conquer the Inca empire.

The following outline of the major battles of South-East Africa is taken from Malyn Newitt’s ‘A History of Mozambique.’ (pages are shown in brackets)

Map showing Portuguese colonial possessions and settlements in south-east Africa, and the different invasions by various Portuguese armies (in red), and the counter-attacks by African armies (blue).

The ruins of Chisvingo in Zimbabwe

In 1572, Francisco Barreto's army of 1,000 Portuguese horsemen and musketeers, supported by numerous African auxiliaries, travelled up to the Sena River until its advance was checked by the Maravi. Another expedition with 700 musketeers in 1573, with even more African auxiliaries and cavalry, managed to score some victories in Manica region but eventually retreated, sending another expedition with 200 musketeers that was massacred by an interior force. By 1576, the last remaining Portuguese soldiers from this expedition had left (pg 57-58)

In 1607-1609, the Portuguese under Diogo Simoes Madeira obtained a grant from the Mutapa king Gatsi Lucere over all the mines of the kingdom in exchange for the military assistance, which he had offered, which included 100 musketeers. This, in effect, made Mutapa a Portuguese colony, although internal divisions among the Portuguese allowed Gatsi to retain significant autonomy (pg 83-85)

In 1628-1631, the Portuguese deposed Gatsi’s son, King Kapararidze, and installed King Mavura as their puppet. An anti-Portuguese revolt swept across Mutapa led by Kapararidze, resulting in the deaths of 300-400 Portuguese scattered over the Mutapa territory. (pg 90)

In 1632, the Portuguese under Diogo de Sousa de Meneses arrived with 200-300 musketeers and 12,000 African auxiliaries. They reestablish Portuguese control over Quelimane and Manica and succeed in defeating Kaparidze and reinstalling Mavura from whom they obtained tribute, effectively securing their colony (pg 91-92)

In 1684, the emerging Rozvi kingdom’s ruler Changamire scored a major victory against the Portuguese musketeers at Maungwe, with a force armed with only bows and arrows.39

In 1693, a combined Rozvi-Mutapa force descended upon the Portuguese settlements in Mutapa, such as Dambarare, resulting in the massacre of Portuguese settlers and forcing survivors to retreat to Tete. This attack effectively ended the colony of Mutapa, about 5 years before the capture of Fort Jesus resulted in the loss of their East African possessions. (pg 103)

In 1695, the Rozvi forces descended on Manica and sacked the Portuguese settlements there, sending refugees scurrying back to Sena just as other regions like Kiteve were driving out the Portuguese. By the early 18th century, the Portuguese settlements were confined to Mozambique’s section of the Zambezi River. (pg 104)

It wasn’t until the late 19th century that the Portuguese reestablished control in the Zambezi valley of Mozambique. (pg 296).

Across West, East, and Central Africa, the “superior technology” of the Portuguese proved largely ineffective on the battlefield. Likewise, disease alone did not constitute a decisive barrier to European colonization, as demonstrated by long-standing Portuguese settlements in Angola, Benguela, and Tete, which persisted for over four centuries in some of the most malaria-prone regions of the continent.

Instead, the emergence of large-scale colonial settlements, characteristic of late 19th-century Africa, was constrained primarily by the strength of African armies, which repeatedly repelled European incursions and maintained local political autonomy.

Africa’s geographic orientation: comparing the rate at which plant and animal domesticates were dispersed across the continent.

Jared Diamond argues that Eurasia’s unique geographic axis of orientation fueled the “rapid” spread of food production from the fertile crescent to western Europe, at a rate of 0.7miles per year (1.1 km/year), while a similar spread of domesticates from Mexico to south-west US, occurred at a “slow” rate of 0.5 miles per year (0.8km/ year).

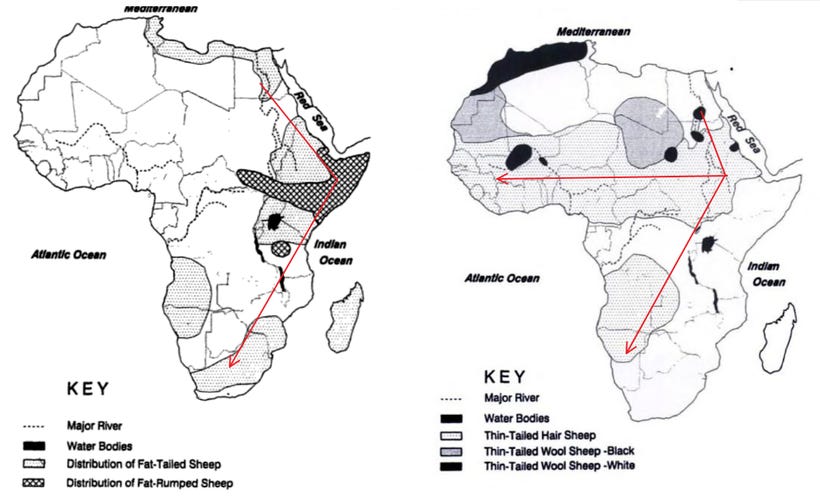

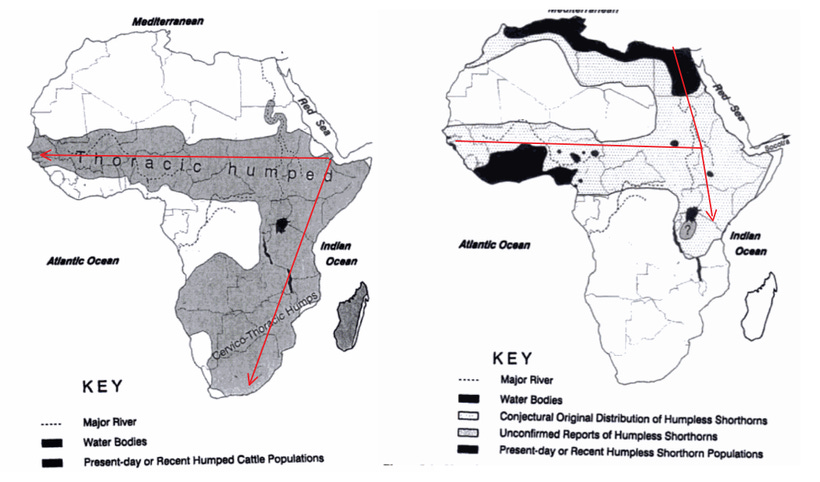

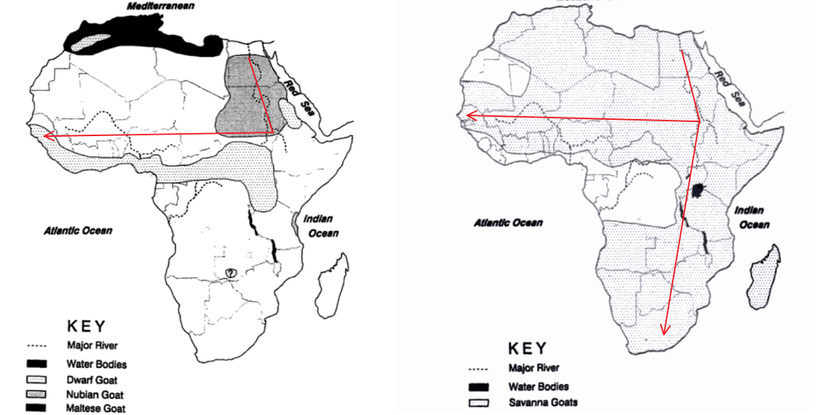

He acknowledges that Africa had its own independent agricultural revolution in west and east Africa from where African crops we carried southwards, but concentrates most of his interest on the spread of domesticated animals introduced from western Asia (cattle, sheep, and goats), which he claims didn’t travel across Africa as fast as they did to western Europe. (GGS pg 186-187)

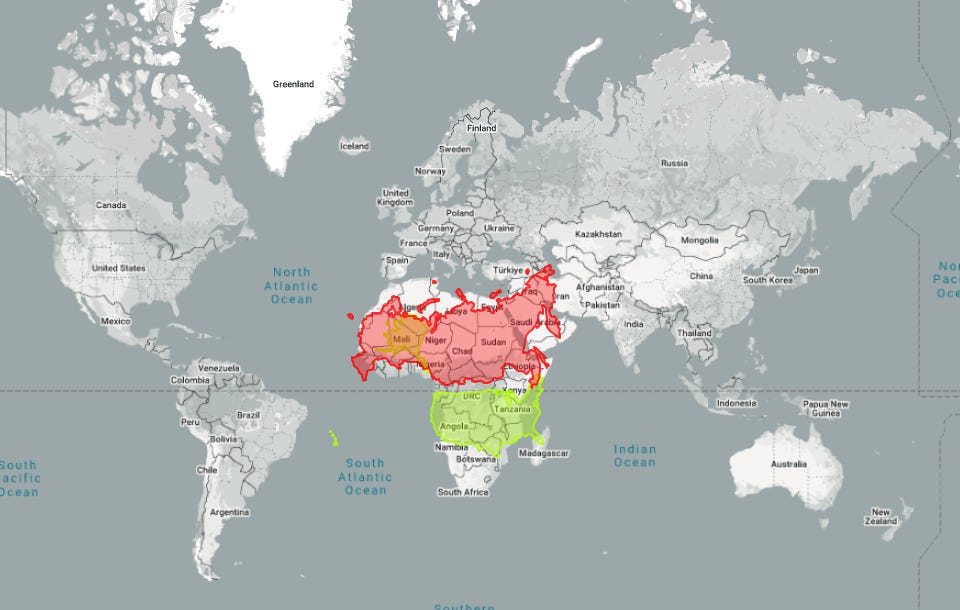

It is rather surprising that Jared Diamond, a professor of geography, utilizes a very distorted world map, which is based on the Mercator projection that misrepresents the true size of Africa relative to Eurasia. Perhaps knowing that using a map which shows Africa’s true size and orientation would undermine his central argument.

Map of continental orientations according to Diamond. (The red line from Senegal to Somalia was added by me)

In reality, Africa is almost as wide as Eurasia. The straight-line distance between Dakar (Senegal) and Ras Hafun ( Somalia) is 7,458 km, and is about is about 94% the distance between Brussels and Beijing at 7958. The continent is also exactly as wide as it is long. The straight-line distance between Tripoli and Cape Town is 7448 km, nearly the exact length between Senegal and Somalia.

This misleading but popular Mercator projection is one of the reasons why the African Union is backing a campaign to adopt a world map that more accurately reflects the continent’s relative size.

Russia and the United States overlaid on a Map of Africa.

The ‘Equal Earth projection’ favoured by the African Union

Diamond doesn’t provide specific figures for his claims that the spread of African food production was slow, but we can use his definition of rapid vs slow rate for Europe and America, (ie; 1.1km/yr vs 0.8km/yr) and apply it to Africa by measuring straight-line distances separating the earliest known sites where the animals were introduced to the furthest western and southern site where they were spread.

Maps of straight-line dispersion routes of domesticated animals in Africa.

*Note that these arrows aren’t the actual paths taken by the domesticates, nor do the end points of the dispersion denote real archeological sites, but approximate locations and routes similar to those used by Diamond to derive his calculations of what he considered “rapid” vs “slow” dispersion rates.

The Maps and routes are taken from Roger Blench’s ‘Ethnographic and linguistic evidence for the prehistory of African ruminant livestock, horses and ponies’, published in The Archaeology of Africa (1993), while the dates are taken from The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology (2013), edited by Peter Mitchell (pages shown in brackets)

Goats were introduced in Sudan by 5000BC and were in Ghana’s Kitampo region nearly 4,000 km west by 2,000 BC (pg 494-5)

North-East-West spreading Rate = 1.3km/year (rapid)

Sheep arrived in North Africa in 5000BC and were in South Africa, nearly 6,000 km south by 500BC (pg 495-496)

North-South spreading Rate = 1.2km/year (rapid)

Cattle were in northern Sudan by 5000BC, and by 2500BC were in Mali about 3,000 km west (and in northern Tanzania), reaching South Africa by the 1st century BC, about 6,000 km south (pg 529, 609, 586, 646)

East-West rate = 1.2km/year (rapid)

North-South rate = 1.2km/year (rapid)

As demonstrated above, the estimated rates of domestication dispersion across Africa proceeded at roughly the same pace as in Eurasia, based on Diamond’s rate of 1.1 km per year. Admittedly, these are rough, back-of-the-envelope calculations that would not satisfy the rigor expected by professional archaeologists. Yet it is precisely this kind of simplistic methodology that underpins Diamond’s ambitious, but ultimately erroneous, grand theory.

Conclusion: The limits of Geographic determinism in Africa

Jared Diamond demonstrates considerable ingenuity in attempting to substantiate his arguments, yet ultimately achieves far less than he ambitiously claims.

His framing of African history as a puzzle appears to be guided less by engagement with the existing historiography than by the “arrogance” of historical realities on the continent, which consistently defied his tidy theoretical assumptions.

Contrary to Diamond’s most emphatic supporters, the historical evidence outlined above demonstrates that Geography isn’t Destiny. The trajectory of African societies was influenced as much, if not more, by human factors than by the continent’s physical configuration.

On 25th December, 1820, a visitor to the kingdom of Warri (S.W Nigeria) saw “at Christmas a great procession which went from the town to a small village carrying a crucifix and some other symbols of Christianity.”

This religious festival, observed in a society that had gone more than half a century without a visiting priest, offers a striking illustration of the persistence of Christian traditions in pre-colonial West African societies.

The history of Christianity in pre-colonial West Africa is the subject of my latest Patreon Article. Please subscribe to read about it here:

n

Beyond ‘Khoisan’: Historical relations in the Kalahari Basin, edited by Tom Güldemann and Anne-Maria Fehn, pg 2-3

Bantu Authorities: Apartheid’s System of Race and Ethnicity, by Ehrenreich-Risner

Beyond ‘Khoisan’: Historical relations in the Kalahari Basin, edited by Tom Güldemann and Anne-Maria Fehn, pg 24-31

Malawi and eastern Zambia before the Bantu W.H.J. Rangeley’s “Earliest Inhabitants” revisited 50 years on by John Kemp Part 2 pg 2-3. The Bantu Languages by Mark Van de Velde pg 4-5, An Early Divergence of KhoeSan Ancestors from Those of Other Modern Humans Is Supported by an ABC-Based Analysis of Autosomal Resequencing Data by Krishna R. Veeramah et a.l, pg 626

Archaeogenetics of Africa and of the African Hunter Gatherers by Viktor Černý and Luísa Pereira pg 9-10

Margarida Coelho; On the edge of Bantu expansions, pg 8,13, Černý Luísa Pereira, Archeogenetics of Africa pg 10

Linguistic Evidence for the Introduction of Ironworking into Bantu-Speaking Africa by Jan Vansina, pg 322-323.

A critical reappraisal of the chronological framework of the early Urewe Iron Age industry by Bernard Clist.

Three Decades of Iron Age Research in South Africa: Some Personal Reflections by Tim Maggs. A Review of Recent Archaeological Research on Food-Producing Communities in Southern Africa by Tim Maggs. The Temporal Distribution of Radiocarbon Dates for the Iron Age in Southern Africa by John C. Vogel.

Excavations at Silver Leaves: A Final Report by M. Klapwijk and T. N. Huffman

Indigenous African Metallurgy: Nature and Culture by S. Terry Childs and David Killick, pg 321-322.

Population collapse in Congo rainforest from 400 CE urges reassessment of the Bantu Expansion by Dirk Seidensticker et al., pg 8

The Bantu Expansion by Koen Bostoen (2018), pg 9

The Cape Herders: A History of the Khoikhoi of Southern Africa by Emile Boonzaier pg 52-56

Imagining the Cape colony by David Johnson pg 10-20, The Cape Herders: A History of the Khoikhoi of Southern Africa by Emile Boonzaier pg 59-60)

An Archaeology of Colonial Identity by Gavin Lucas pg 69-72, The Cape Herders: A History of the Khoikhoi of Southern Africa by Emile Boonzaier pg 77-78)

Masters and Servants on the Cape Eastern Frontier, 1760-1803 By Susan Newton-King. Slavery in South Africa: Captive Labor on the Dutch Frontier By Elizabeth A. Eldredge and Fred Morton

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 59-62)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge, pg 63-67, Records of South-Eastern Africa Collected in Various Libraries and Archive Departments in Europe · Volume 1 edited by George McCall Theal pg 260-261

Bokoni: Old Structures, New Paradigms by P Delius, T. Maggs, A. Schoeman pg 405

The Late Iron Age Sequence in the Marico and Early Tswana History by Jan C. A. Boeyens pg 68-71

Bokoni: Old Structures, New Paradigms by P Delius, T. Maggs, A. Schoeman pg 411, Forgotten World: The Stone-Walled Settlements of the Mpumalanga Escarpment by Peter Delius pg 12-24

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge, pg 145-148

A Military History of South Africa From the Dutch-Khoi Wars to the End of Apartheid By Timothy J. Stapleton pg 4-11, 18, 27-29

The House of Phalo: A History of the Xhosa People in the Days of Their Independence By Jeffrey B. Peires pg 18-24

The House of Phalo: A History of the Xhosa People in the Days of Their Independence By Jeffrey B. Peires pg 20-21, Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 77-78, Africa In The Days Of Exploration by Oliver, Roland pg 131

The House of Phalo: A History of the Xhosa People in the Days of Their Independence By Jeffrey B. Peires pg 27-29, 59-67

The Hadza: Hunter-gatherers of Tanzania by Frank Marlowe pg 17-33

La révolution agricole des Pygmées aka by Guille-Escuret

Hunter-gatherers: an interdisciplinary perspective by Catherine Panter-Brick, pg 301-302)

Cattle theft in Christol Cave : A critical history of a rock image in South Africa by Jean-Loïc Le Quellec et al.

Europeans and Africans: Mutual Discoveries and First Encounters By Michał Tymowski pg 35-37, The Chronicle of the discovery and conquest of Guinea 2, by Gomes Eanes de Zurara, pg 252-254, 258-261

The voyages of Cadamosto and other documents on Western Africa in the second half of the fifteenth century By Alvise Cà da Mosto, Antonio Malfante, Diogo Gomes, João de Barros

Warfare in Atlantic Africa, 1500-1800 By John Kelly Thornton pg 43, 56-57, 77-78, 84-85)

The Portuguese in West Africa, 1415–1670 A Documentary History by M newitt, pg 217, Eurafricans in Western Africa : Commerce, Social Status, Gender, and Religious Observance from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century By George E. Brooks pg 74-75, Africa Encountered: European Contacts and Evidence, 1450–1700 By P.E.H. Hair pg 59-60, n.24)

The Art of War in Angola, 1575-1680 by John K. Thornton pg 377

Angola’s population of 1,581 whites in 1777 had been surpassed by the Cape Colony in 1713, although the former grew little and can be assumed to have been about 1,300 in 1700, roughly equal to the Cape white population of 1,265 in 1701.

Angola Under the Portuguese The Myth and the Reality By Gerald J. Bender pg 20. The `White’ Population of South Africa in the Eighteenth Century By Robert Ross, pg 221)

The Art of War in Angola, 1575-1680 by John K. Thornton pg 378

Portuguese Musketeers on the Zambezi by Richard Gray, pg 533)

Every time I’ve read a subject matter expert engage with Diamond, the result is the same. His facts are so wrong, and so sloppily wrong, that they don’t even know where to start. Your argument here is the most respectful I know of, and you’ve still broken down Diamond’s arguments at every step of the way.

However, I’m left a little discontented. Diamond captured so much attention by asking a really big and important question, and supplying a single rubric to answer it with. Everyone close to the issues he glosses over find his scholarship appalling— *but nobody tries to answer his fundamental question*— in general (why did Europe conquer the global south?) or in particular (why did Europe conquer Africa, say, in the places and times that it did?)

Your conclusion seems to point in the direction of this kind of answer(s), and that’s what I was most curious to hear. What are the human factors that made European societies dominate African ones when they did (after, as you say, failing to dominate them for 300+ years)? Is there an essential pattern to the answers you find, or do you think the interactions of the colonial era were just a more diffuse set of political interactions without any overarching pattern?

Worth reading — but it shows the risk of “big explanations.” Africa’s history isn’t a single story you can reduce to geography. Power, choices, migrations, and systems all mattered — and the newer evidence complicates the neat narrative.